Faizan Ul Haq is currently a Senior at LUMS majoring in History. His interests include tech, philosophy, and social justice

A non-exhaustive database of mobile phone applications developed by the Pakistani government has been compiled by Faizan and can be accessed here.

It has been widely noted that Pakistan’s potential for IT development has grown vastly in the last decade or so. According to the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority’s Annual Report for 2019-2020, in the period from 2016 to 2020, Mobile phone data usage in Pakistan has increased from 614 petabytes to 4,498 – an increase of over 700% in just half a decade. In the same time period, the distribution of broadband services has doubled. While numerous reasons can be speculated for leading this change (from the availability of cheaper smartphones from Chinese providers like Q-Mobile and Huawei, to the increasing importance of IT in business development, and the proliferation of mobile internet), it is obvious either way that the digital world in Pakistan now presents a new avenue that can be harnessed for better governance and delivering services.

It makes sense, then, that in late 2019, Prime Minister Imran Khan inaugurated the “Digital Pakistan” initiative. In its policy objectives, what stands out is the emphasis towards using digital applications (henceforth referred to as apps) for “e-governance” and in “key socio-economic sectors”. While there have been a few apps released previously to help with the aforementioned, the current government is seems intent on maximizing this newfound potential.

Over a 100 different apps (as of the summer 2021) have been released on the Google Playstore for Android phones and the Apple store for iOS device by both the government, at the provincial, federal and, at times, the district level. Primarily developed by different provincial IT boards, they cover a wide range of functions including education, the regulation of pre-existing government bodies, agriculture, and online ticketing and booking. Some apps are meant only for citizens of a particular locale (such as the City Islamabad app), while others are targeted to people of a specific profession (the Lahore and Sindh High Court apps are targeted towards the legal community). A few apps have also been released to help deal with health and safety emergencies, such as the Baytee app meant to increase women’s safety and a number of apps aimed at helping track and register COVID cases in Pakistan.

However, just publishing apps does not immediately mean that those apps have helped fix the underlying issues, or that they have been effective in their stated objectives. Quite a few of these apps have dubious efficacy, and some appear to not work at all. There are a few clear trends as to which apps have worked and which have not.

A number of apps profess a wide range of features. The “City Islamabad” app promises a lot. With the goal of “bridge(ing) the gap between citizens and government” by removing the need to go to government offices to access public services and departments, the app is supposed to provide quick access to numerous forms and payment services that would otherwise would have only been available therein. In practice, the Playstore review page is full of complaints that not all of the forms actually work. People have pointed out that tokens generated aren’t always registered by relevant financial departments. Certain forms load indefinitely – either they have not been programmed in properly, or the forms just are not available on the app. At the same time though, certain key features of the app still work and function effectively. The part of the app that provides information on Islamabad’s major landmarks and public facilities loads instantly and provides accurate information, while a portion of the userbase reports successful payment of tax related tokens and response upon submitting complaints. It appears that while a wide number of features have been programmed in, not all of them are perfectly useable.

A similar issue exists with what is arguably the government’s flagship application, the Pakistan Citizen Portal. Most of the reviews posted in September and August 2021 are entirely negative and allude largely to the same issue: a large number of the complaints registered on the app do not actually appear to lead to anything concrete and are instead marked “resolved” without any appropriate action being taken. While this is likely not representative of all users who have used the app, it does imply a degree of miscoordination between the app’s complaint registration mechanism and the departments that are meant to cater to it. If it’s true that complaints being marked as resolved does not actually mean any action has been taken, the widely quoted statistics on the application’s website need to be taken with a grain of salt, it’s unlikely that each of the 3.1 million . It also speaks to the limitations inherent in e-governance and service delivery through apps – the issues that are already present in government bodies are likely to be reproduced through the functioning of the app. For example, if government bodies continue to treat cases of harassment lightly because of misogynistic attitudes, then the solution lies in a structural reform of said government bodies instead of opening more digital portals to file complaints through.

On the contrary, apps that are targeted towards a specific group of people appear to have had more success. There are two broad types of apps like this: some that have been created solely for the use of people in certain government departments, and others for everyone who works in a particular profession. Apps in the former category include the “Price Magistrate” app – a complaint management app meant specifically for district magistrates. This app has seen less use compared to other apps on this list, and its review section is full of users confused at the lack of a registration option. Of the few reviews that do appear to be from its intended user base, it seems that the app functions well.

An app’s functionality however is not just defined by how well certain features work. Overtime, as more bugs are reported, new devices are released and as operating systems go through several iterations, the publisher needs to provide constant support through updates to ensure their functionality. This is especially important in Pakistan, where Android users are likely to be using a very diverse set of devices given the numerous smartphone companies that exist. Additionally, smartphones in different price ranges have specific limitations – differences in screen resolution, RAM, processing power, and networking features mean that developers need to ensure that their apps can work despite these limitations. If this diversity isn’t catered for, sections of the Pakistani population that can only afford cheap smartphones with weaker specifications are likely to be left out. This means that the demographic which is least likely to be digitally literate will now also face bugs and compatibility issues that make it harder for them to use these applications. Updates are also important to address any security issues on the app, most application updates are issued to fix security bugs that are discovered later on and unanticipated backdoors.

The most prolific publisher of Government apps thus far has been the Punjab IT Board (compared to the other regional boards and other publishers, who barely have half as many apps as the Punjab board between them). On their Android publisher page alone, they have over 70 apps published. Yet, their support for these apps has been sporadic. More than half of these have not been updated even once in 2021. While at best, this might lead to most of these apps functioning albeit with bugs, quite a few of them have been rendered completely unusable as a result. A large number of users report that quite a few of these apps no longer have a working system for logging in users owing to an issue in generating and processing an OTP key. Other apps have been rendered completely unusable – the Agri-Smart app has been rendered completely unusable for certain Android users since their devices’ IMEI codes cannot be accessed. These issues have remained unaddressed for months on end.

It is unclear what the status of these apps is – if such glaring issues exist, has support for them been dropped completely? This seems to be the case, because other apps have had the publisher release frequent updates and engage with reviews that have pointed out issues. The fact that these apps remain available for download despite issues with their usability and a lack of developer support is troubling and speaks to a pattern where apps are launched without the necessary infrastructure to conduct follow-ups. This has caused a fair amount of confusion on app stores, as people continue to download said apps and leave negative reviews because of the clear lack of functionality.

If this is demonstrative of a communication gap between app developers and the intended user base, it is not the end of it. Certain apps certainly seem like they are designed to be used by a large user base, but evidently have not been used as such. The Click ECP app meant to facilitate voters during each election cycle and the Covid-19 Tracker app for Lahore both remain with only over a 1000+ downloads on the Playstore, when it is intuitive that their usage numbers should be far in the thousands. The “Equal Access App” meant to help disabled individuals also remains unused as its user base still is unengaged. At best, this is likely to result in certain apps being unused by their target demographic. At worst though, this can open the door to privacy violations.

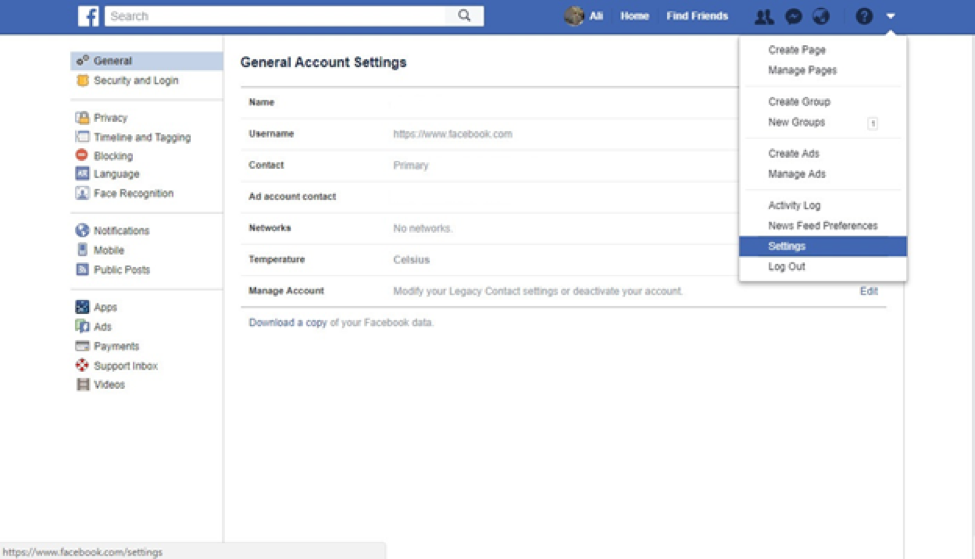

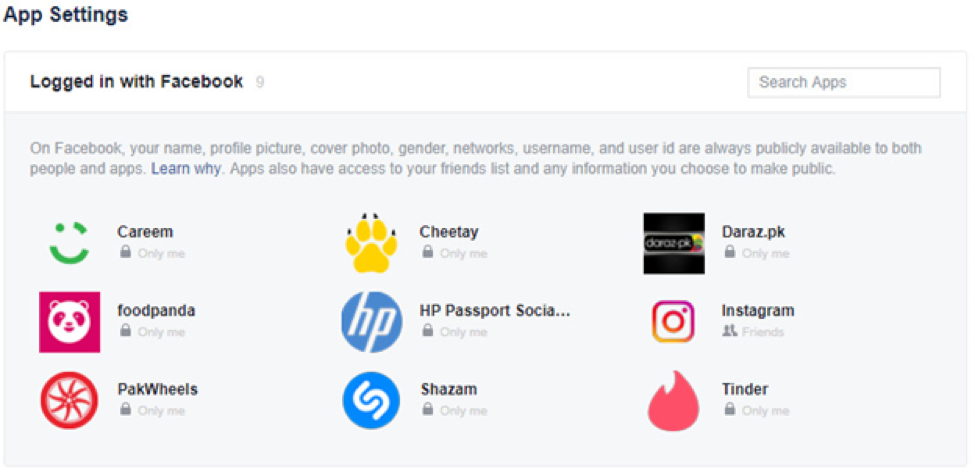

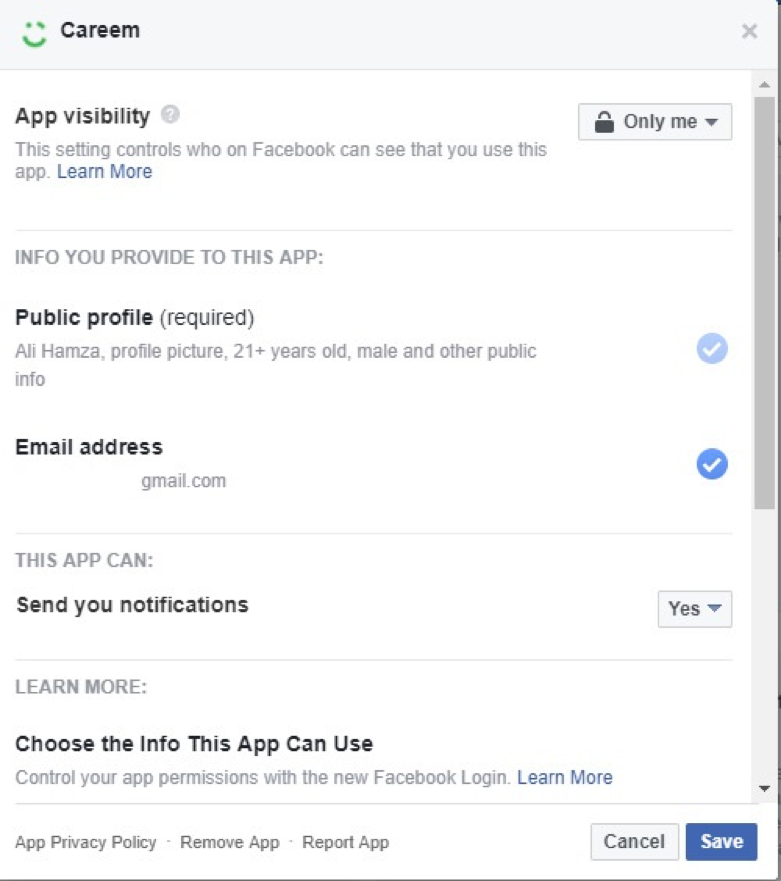

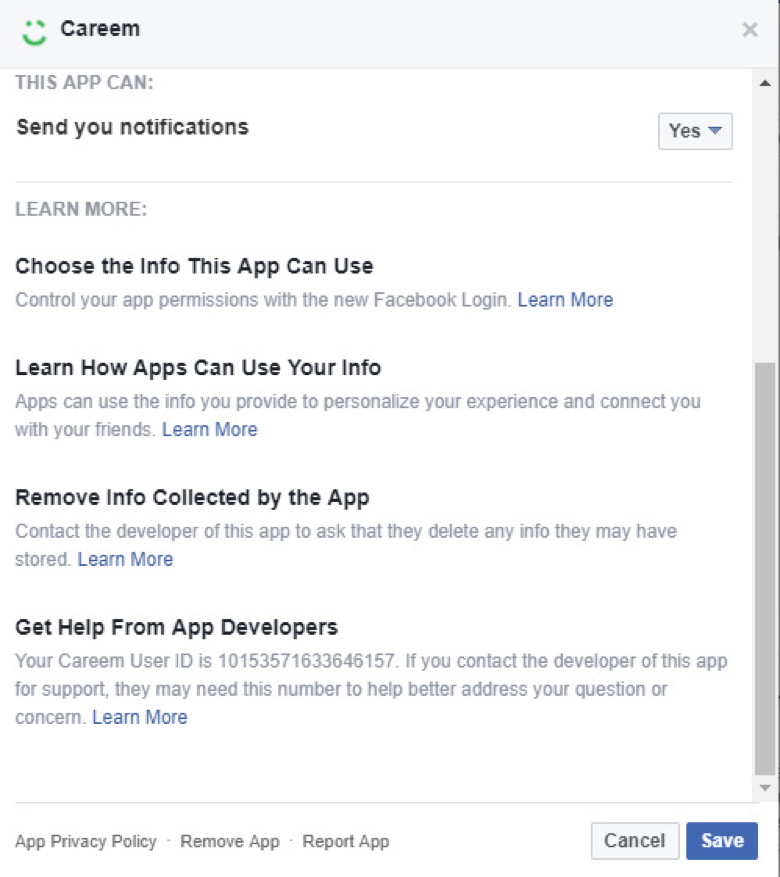

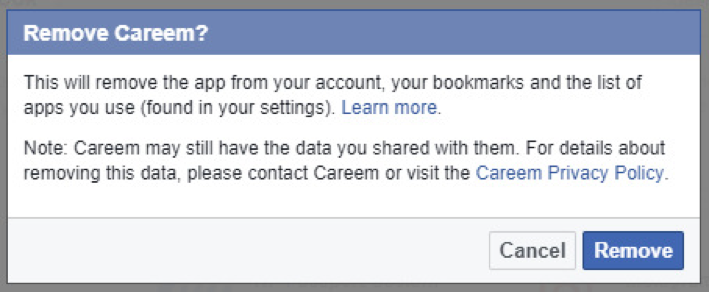

Upon first use, a lot of apps require permission to access certain information and features of a phone. While this can vary from app to app, the general rule of thumb is that apps tend to only ask for those permissions that are core to an app’s functionality. Instagram, for example, will only ask for permission to use your camera when you open the in-app camera for the first time. However, even this can run awry – the Facebook app has long been under suspicion for secretly recording conversations for advertisement purposes. A number of apps supported by the Pakistan government, however, ask for a lot of permissions right at first launch. The Pehchaan app (currently unavailable on the Playstore as of September 2021) immediately requests permission to access a user’s location on launch. The “Forest Management Information System” (FMIS) app requests not only access to location services, but also to use the phone’s camera, to “modify and delete contents” of media files saved on device or USB storage, and of Wi-Fi connections. Why the app requires any of this is puzzling, especially since there is no use for any of these features immediately after an app has been launched. This runs afoul of the Principle of Data Minimization – the idea that data collectors should only request and use data that is needed for a specific purpose. Ideally, that purpose should be communicated clearly and a privacy policy should be attached in any scenario where private data is needed. Given that there is little communication from the developers of why these permissions are needed in the first place, it’s extremely troubling that many people in Pakistan could agree to these permissions just to launch an app without realizing the extent to which their privacy is invaded. While Google Play store does include a requirement that each app have a privacy policy attached, the Punjab IT Board’s Privacy Policy seems inadequate. The fact that it’s a generic policy means that it does not cater to the way each individual app may request, use, and store user data. By contrast, the City Islamabad App’s privacy policy and the Pakistan Citizens Portal’s privacy policy at least both specify the kind of data that may be collected. The Punjab IT Board’s privacy policy might already be violated by the FMIS collecting the “the minimum amount of information” required by the app. It is clear that the Punjab IT Board’s privacy policy – under which most of the apps released so far fall under – can be comprehensive and applied more rigorously.

Ultimately, the legitimacy of the Digital Pakistan initiative is worth questioning. Despite the massive growth in Pakistan’s access to these digital technologies and the potential therein, the system put in place to actualize it deserves further scrutiny. The reception of apps published by the government needs to move beyond a tokenistic celebration of each app’s release, to an evaluation of their actual benefit and long-term functioning.