Position Paper by Digital Rights Foundation

June 4, 2021

These comments are with reference to the concept paper circulated by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (“MOIB”) titled “Concept Paper for Establishment of Pakistan Media Development Authority (PMDA)” dated May 19, 2021, and the “Pakistan Media Authority Ordinance, 2021” (the “Ordinance”) dated May 7, 2021.

The proposed Ordinance is a blatant attempt to exercise excessive control over the media in order to “manage” freedom of expression through licensing of content producers, stamp out dissent through expansive and vague terms and conditions, and imposing onerous restrictions and punishments through excessive fines and sentences. Under the garb of ensuring efficiency and eliminating red tape, the government seeks to centralise controls over the media. However, these efforts are completely misguided and utterly unenforceable in the era of digital media, where content production and news making is decentralized. Additionally, imposing a licensing regime for journalists amounts to censorship and violation of settled international norms.

Law by Ordinance is an Extraordinary Measure

Digital Rights Foundation (“DRF”) opposes the Ordinance at a fundamental level as centralisation of regulatory authority is a draconian move and runs afoul to the fundamental freedoms enshrined in the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 (the “Constitution”) particularly freedom of expression (Article 19) and right to information (Article 19A). At the onset, the method followed by the state to pass the law via ordinance, as opposed to an Act of Parliament, bypasses democratic processes and checks and balances in place. The power of the President, enshrined under Article 89 of the Constitution, is an extraordinary one to be exercised only when the Senate or National Assembly are not in session and it is necessary to take immediate action. Nothing in the text of the Ordinance and accompanying concept paper identifies the need for immediate action to the clear structural and long-term issue of media regulation. We fail to understand what emergency exists with regards to the media that would necessitate such extraordinary actions. This short-cut method of passing legislation without input from the opposition is fundamentally undemocratic and has become the modus operandi of the ruling government. Furthermore, given that Ordinances expire after a period of 120 days, this Ordinance is a stop-gap effort, at best, and a way to pass legislation unilaterally at its worst. Additionally, the Ordinances proposes sections that allow the Federal Government to issue directives (S. 5)[1], engage in excessive delegation to determine speech rights relating to constitutional rights through the latter creation of a ‘Code of Conduct’,[2] and grant wide powers to make Rules.[3] The Authority also has been given a carte blanche to grant exemptions from any provisions of this Ordinance where it deems there are sufficient grounds in the name of ‘public interest’.[4]

Curtails Freedom of Expression

Moreover, the Ordinance fails to fulfil its own objectives as stated in the preamble. The lofty objectives of ensuring the “Constitutional guarantee of freedom of speech and expression” cannot be guaranteed through overly broad legislation that sets terms and conditions for license holders of electronic, digital and print media. These terms

S. 5: “Power of the Federal Government to issue directives. – The Federal Government may, as and when it considers necessary, issue directives to the Authority on matters of policy, and such directives shall be binding on the Authority, and if a question arises whether any matter is a matter of policy or not, the decision of the Federal Government shall be final”

S. 20: “Licenses, Registration Certificates, declaration and NOC for media services and films: (5) The Authority shall devise a Code of Conduct for programmes and advertisements for compliance by the licensees or registration certificate.”

S. 48: “Power to make rules. - (1) The Authority may, with the approval of the division concerned, by notification in the official Gazette, make rules to carry out the purposes of this Ordinance.”

S. 39: “Power to grant exemptions.- The Authority may grant exemptions from any provisions of this Ordinance, where the Authority is of the view that such exemption serves the public interest and the exemptions so granted shall be supported by recording the reasons for granting such exemptions in writing provided that the grant of exemptions shall be based on guidelines and criteria identified in the regulations and that such exemptions shall be made in conformity with the principles of equality and equity as enshrined in the Constitution.”

contain vague criteria such as the “preservation of the sovereignty, security and integrity of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan”[1], “preservation of the national, cultural, social and religious values”[2] and restrains on material relating to “violence, terrorism, racial, ethnic or religious discrimination, sectarianism, extremism, militancy, hatred, pornography, obscenity, vulgarity or other material offensive to commonly accepted standards of decency”[3] and “prejudicial to the ideology of Pakistan or sovereignty, integrity or security of Pakistan.”[4] While Article 19 of the Constitution allows for reasonable restrictions as per law on the freedom of expression, it is a well-settled principle of law that restrains on fundamental rights need to be narrowly-tailored and carefully defined so as not to lend itself to undue censorship by those in power.[5] Furthermore, there are restrains on any of the licensee from defaming or bringing “into ridicule the Head of State, or members of the armed forces, or legislative or judicial organs of the state,”[6] which will have the direct effect of styming democratic discourse and public debate given that public figures and institutions are supposed to withstand a higher degree of scrutiny, criticism and even defamation than the average citizen.[7]

S. 21: “Terms and conditions of license or registration certificate or declaration or NOC. - (a) Conditions requiring the licensee registration certificate or declaration or NOC to ensure preservation of the sovereignty, security and integrity of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan”.

S. 21(b): “Conditions to ensure preservation of the national, cultural, social and religious values and the principles of public policy as enshrined in the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan”.

S. 21(c): “Conditions to ensure that all programmes and advertisements do not contain or encourage violence, terrorism, racial, ethnic or religious discrimination, sectarianism, extremism, militancy, hatred, pornography, obscenity, vulgarity or other material offensive to commonly accepted standards of decency.”

S. 21(l): “Conditions requiring the licensee to ensure that no anchor person, moderator or host propagates any opinion or acts in any manner prejudicial to the ideology of Pakistan or sovereignty, integrity or security of Pakistan.”

UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 34, Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, 12 September 2011, CCPR/C/GC/34. [General Comment No. 34]. Accessed June 4, 2021: https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/docs/gc34.pdf.

Para 21: “However, when a State party imposes restrictions on the exercise of freedom of expression, these may not put in jeopardy the right itself.”

Para 25: “For the purposes of paragraph 3, a norm, to be characterized as a “law”, must be formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate his or her conduct accordingly and it must be made accessible to the public. A law may not confer unfettered discretion for the restriction of freedom of expression on those charged with its execution.”

S. 21(n): “Conditions requiring the licensee to not broadcast, distribute or make available online anything which defames or brings into ridicule the Head of State, or members of the armed forces, or legislative or judicial organs of the state.”

General Comment No. 34, para. 38: “concerning the content of political discourse, the Committee has observed that in circumstances of public debate concerning public figures in the political domain and public institutions, the value placed by the Covenant upon uninhibited expression is particularly high. Thus, the mere fact that forms of expression are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify

Economic fallout on Digital Media

A fundamental flaw in this Ordinance is that it is attempting to regulate all forms of media in the same manner. Given the complex and constantly evolving nature of the internet, it is impossible to regulate online platforms through frameworks that have been designed for other (offline) mediums. For instance, amateur news gatherers or bloggers cannot be treated and regulated in the same manner as big news media companies. This point was also noted in the Joint Declaration (2011) of special international mandates for freedom of expression that: “Approaches to regulation developed for other means of communication - such as telephony or broadcasting-cannot simply be transferred to the Internet but, rather, need to be specifically designed for it”.

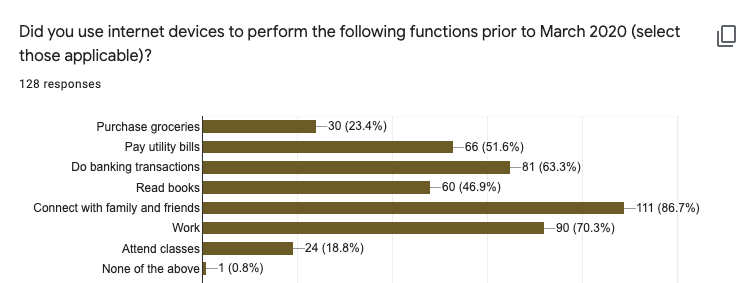

The economic impact of this legislation will be nearly fatal, disproportionately affecting digital media outlets and content producers who do not have the resources to ensure registration and pay fees. If the government is serious about its objective of creating “a robust environment for the development of all forms of media, having competition, plurality of voices, diversity of opinions,” then this approach is wholly unsuited for the stated aim. A licensing regime that allows for wholesale restrictions on a channel, publication, website or account as opposed to particular content is unduly restrictive.[1] Furthermore, the Ordinance fundamentally misunderstands how digital media works, the broad definitions of terms such as ‘Broadcaster’ (s. 2(f)),[2] ‘Media’ (s. 2(ta))[3], and ‘Digital Media’ (s. 2(ua))[4] will essentially mean any internet user who produces content relating to “news & current affairs, entertainments, sports, regional language, education, agriculture, health, specialized subject, kids, travel

the imposition of penalties, albeit public figures may also benefit from the provisions of the Covenant. Moreover, all public figures, including those exercising the highest political authority such as heads of state and government, are legitimately subject to criticism and political opposition.”

General Comment No. 34, para. 39: “It is incompatible with article 19 to refuse to permit the publication of newspapers and other print media other than in the specific circumstances of the application of paragraph 3. Such circumstances may never include a ban on a particular publication unless specific content, that is not severable, can be legitimately prohibited under paragraph 3.”

“Broadcaster” means a person engaged in broadcast media and digital media.

“Media” means broadcast, print, digital communication channel through which information, entertainment, education or promotional messages are disseminated and includes the electronic, print and digital media.

“Digital media” means any information or content that is broadcast including text, audio, video, graphics, web TV, over the top TV and other such content made available for viewing over the internet.

& tourism, science and technology etc” will be required to acquire “licenses, registration certificates, declaration and No Objection Certificates.” This ‘prior restraint’ model of speech is unduly restrictive and imposes unnecessary barriers to free speech.

As aforementioned, there seems to be a comprehension problem about how digital markets work which is why traditional competitive practices cannot apply to them. The anachronistic competition laws that are designed for local markets cannot be extended to online platforms with a global outreach. Moreover, some online platforms are offering free services to their users, hence, the standard competition criterion of excessive pricing will not be applicable to them.

Prior Restraint Licensing Model

Additionally, the proposed licensing regime is subject to a great degree of uncertainty as the PMDA has the discretionary powers to alter the terms and conditions of the license in the public interest.[1] Licensing of journalists is completely different from licensing media houses, the licensing scheme that the Ordinance envisions would be “susceptible [to] abuse and the power to distribute licences can become a political tool. While the purpose of licensing schemes is ostensibly to ensure that the task of informing the public is reserved for competent persons of high moral integrity, the Inter-American

S. 19: “Categories of licenses, registration certificates, declaration and No Objection Certificates. - (1) The Authority shall issue licenses for electronic, print and digital media in the following categories, namely: -

(i) National scale;

(ii) Provincial and regional;

(iii) District and Tehsil level;

(iv) Local Area and Community based;

(iv) Specific and specialized subjects;

(v) International scale targeting countries abroad;

(vi) Other categories as the Authority may prescribe from time to time.

(2) The Authority may further sub-categorize the categories specified in sub-section (1) as it may deem fit, such as news & current affairs, entertainments, sports, regional language, education, agriculture, health, specialized subject, kids, travel & tourism, science and technology etc.”

Alain Strowel & Prof. Wouter Vergote,Digital Platforms: To Regulate or Not To Regulate? Message to Regulators: Fix the Economics First, Then Focus on the Right Regulation <https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/image/document/2016-7/uclouvain_et_universit_saint_louis_14044.pdf>

Id.

S. 34(2): “The Authority may vary any of the terms and conditions of the license or registration certificate, declaration and NOC where such variation is in the public interest.”

Court of Human Rights rejected this argument, noting that other, less restrictive means were available for enhancing the professionalism of journalists.”

Furthermore the licensing regime is unduly discriminatory and discretionary. The Authority has a wide berth in terms of deciding licensing fee and validity period of the license. The criteria for persons and entities “not be granted license or registration certificate” includes non-citizens, foreign companies, anyone “funded or sponsored by a foreign government or organization including any foreign non-governmental organization.” This exclusion criterion is in equal parts unsustainable and contradictory. The definition of “illegal operation” in the Ordinance includes any “broadcast, webcast or transmission or operation or exhibition, publishing or printing or distribution of films, newspapers, satellite TV channel, terrestrial TV channels, Over the Top TV channels or a newspaper, or provision of access to, programmes or advertisements or content” without a valid license or registration certificate or declaration or NOC. This essentially means that foreignmfunded or incorporated companies cannot stream content inside Pakistan as they are barred from even obtaining a license. The restriction is even more confusing as the Authority itself can obtain foreign funds, but license holders cannot. The stated objective of this Ordinance “to establish

“BRIEFING NOTES SERIES: Freedom of Expression,” Centre for Law and Democracy, International Media Support (IMS), July, 2014, https://www.mediasupport.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/foe-briefingnotes-ims-cld.pdf.

S. 25: “License/ registration certificate and declaration, NOC application, issuance, refusal and validity. - (4) A license or registration certificate, declaration and NOC for any media service shall be valid for a period of five, ten or fifteen years subject to payment of the annual fee and such other fees as prescribed from time to time and subject to compliance with the provisions of this Ordinance, rules or regulations and terms and conditions of license/ registration certificate.”

S. 26: “Certain persons not be granted license or registration certificate. - (1) A license or registration certificate, declaration and NOC for print, digital media or electronic media service and films shall not be granted to—

(a) a person who is not a citizen of Pakistan or resident in Pakistan;

(b) a foreign company organized under the laws of any foreign government;

(c) a company the majority of whose shares are owned or controlled by foreign nationals or companies whose management or control is vested in foreign nationals or companies; or

(d) any person funded or sponsored by a foreign government or organization including any foreign non-governmental organization.”

S. 2(sc): “Illegal operation” means broadcast, webcast or transmission or operation or exhibition , publishing or printing or distribution of films, newspapers, satellite TV channel, terrestrial TV channels, Over the Top TV channels or a newspaper, or provision of access to, programmes or advertisements or content on any medium including web without having a valid license or registration certificate or declaration or NOC from the Authority.”

S. 15(2): “The Fund shall consist of. - (iv) foreign aid obtained with approval of and on such terms and conditions as may be approved by the Federal Government.”

Pakistan as a major global center for multimedia information and content services” is a non-starter if such provisions remain.

Lack of Independence of the Regulator

Democracies demand that regulators must be independent and free from commercial or political influence so as to ensure that it acts objectively, impartially, and consistently, without conflict of interest, bias or undue influence. However, the Authority is not sufficiently independent from the Federal Government. The members will not only be appointed by the President of Pakistan (S. 6(1)) but will also be removed by the President or Federal Government (s.7(2)) . The members of Authority will rely on the Federal Government for a proportion of its funds (S. 15) which fails to satisfy the legislation’s own aim of creating an “independent, efficient, effective and transparent” Authority. Moreover, the members are also bound to comply with any directives issued by the Federal Government on “matters of policy”, however, whether something constitutes a ‘matter of policy’ cannot be questioned in any court.

Furthermore, the Ordinance creates a confusing structure consisting of the ‘Media Complaints Council’, an ‘Advisory Commission’, and ‘Media Tribunal’. The rationale behind the Advisory Commission, for instance, is unclear in the Ordinance. It is worth noting that the Chairperson and members of the Media Tribunal who will be deciding appeals against orders and decisions of the Authority, will be shortlisted by an Advisory Commission (which includes Chairman of the Authority) (s.27(3)) .

S. 6: “Members of Authority. - (1) The Authority shall consist of a Chairman and eleven (11) members to be appointed by the President of Pakistan on the advice of the Federal Government.”

S. 7(2): “The Chairman or a member may, by writing under his hand, resign from his office. The President or the Federal Government may remove the Chairman or a member from his office if he is found unable to perform the functions of his office due to mental or physical disability or to have committed misconduct.

S. 15. “Fund. - (2) The Fund shall consist of. - (i) Seed money by the Federal Government; [...] (iii) loans obtained with the special or general sanction of the Federal Government;”

S. 27(3 a) Advisory Commission: “It will be composed of four members from the government, four members from stakeholders and chairman of the authority with an advisory role to shortlist panels for members, chairman of Media Complaints Councils as well as Chairman and members of the Media Tribunal as prescribed by the rules.”

S. 27(3): “Advisory Commission: It will be composed of four members from the government, four members from stakeholders and chairman of the authority with an advisory role to shortlist panels for members, chairman of Media Complaints Councils as well as Chairman and members of the Media Tribunal as prescribed by the rules.”

Hence, it is becoming clear that the Government has no interest in ensuring that the regulator and quasi-judicial forums established under this Ordinance are independent.

Arbitrary Powers

Lastly, the punitive powers of the Authority are extensive, overly restrictive and arbitrary. Most egregiously, the Authority has the power to prohibit any person or organization from publishing content “without issuing show cause notice and affording opportunity of hearing”, which violates basic principles of due process and natural justice which are enshrined in the Constitution. The Authority also amasses extraordinary powers to inspect the premises of license holders without any prior notice, a power that would particularly violate the right of privacy for digital content creators who often operate out of their homes and private residence. Furthermore, there is a bar on appealing decisions taken by the various bodies under the Ordinance except for at the Supreme Court. By foreclosing other appellate forums, particularly at the High Court level, it is clear that the Ordinance seeks to consolidate powers in the hands of the government rather than empower media producers. The Ordinance also prescribes punitive measures for violations. It is quite concerning that these penalties such as heavy fines and even imprisonment can be meted out for

S. 28: “Prohibition of print, electronic or digital media service and films operation. - The Authority shall by order in writing, giving reasons thereof without issuing show cause notice and affording opportunity of hearing, prohibit any person, print media, electronic media or digital media service operator or licensee or platform for a period as may be prescribed from –

(a) Printing, Broadcasting, Webcasting, re-broadcasting, distributing or making available online any programme, advertisement or content if it is of the opinion that such particular programme, advertisement or content is against the ideology of Pakistan or is likely to create hatred among the people or is prejudicial to the maintenance of law and order or is likely to disturb public peace and tranquility or endangers national security or is pornographic, obscene or vulgar or is offensive to the commonly accepted standards of decency, this shall also apply to foreign broadcast having landing rights of the Authority or any digital media service operating from abroad but with Pakistan as target market and operating under a license of the Authority; or

(b) engaging in any practice or act which amounts to abuse of media power by way of harming the legitimate interests of another licensee or willfully causing damage to any other person.”

S. 31: “Issue of enforcement orders, imposition of penalties, inspections of any media licensee- (2) The premises of any media licensee or registered entity, declaration and NOC shall, at all reasonable times, be open to inspection by the Authority or any officer under sub-section (1) and the licensee shall provide such officer with every assistance and facility in performing his duties.”

S. 37: “Jurisdiction of courts barred-. Save as otherwise provided by this Ordinance, only Supreme Court of Pakistan shall have jurisdiction to question the legality of anything done or decision or any action taken under the ordinance.”

speech acts.[1] Even more worryingly, these offences, made out under the Ordinance will be cognizable and compoundable.[2]

[1] S. 40: “Offences and penalties. - (1) Any licensee and registered entity, declaration and NOC holder or person who violates or abets the violation of any of the provision of this Ordinance shall be guilty of offence punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years or with a fine which may extend up to two twenty five million rupees or with both.

(2). Where any licensee and registered entity, declaration NOC holder or person who repeats the violation or abetment, such person shall be guilty of offence punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years or with a fine which may extend to TWO Twenty-five million rupees or with both.

(3) Where the violation, or abetment of the violation of any provision of this Ordinance is made by a person who does not hold a license, or registration certificate, declaration and NOC such violation shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years, or with fine upto two twenty-five Million, or with both, in addition to the confiscation of the equipment used in the commission of the act.

(4) Whosoever damages, removes, tampers with or commits theft of any equipment of a media station, printing press or system, cinema houses licensed by the Authority, including transmitting, broadcasting, uplinking apparatus, receivers, boosters, converters, distributors, antennae, wires, decoders, set-top boxes or multiplexers, servers etc. shall be guilty of an offence punishable with imprisonment which may extend to three years, or with fine upto two twenty five million , or both.” [2] S. 43: “Offences to be cognizable and compoundable. - The offences under section 41 shall be cognizable and compoundable.”

Conclusion

While issues relating to the media, freedom of speech and emerging media are thorny and riddled with determinations of the wider public good and the extent of the government’s power to regulate speech. There is no easy answer to these questions. However the unprecedented consolidation and centralisation powers as envisioned under this Ordinance will fundamentally shift the balance of power between the state and media. The passage of this Ordinance will spell disaster for the media in Pakistan, which is already operating within precarious shrinking spaces and in the context of attacks on journalists. Pakistan was ranked 145 in in the World Press Freedom Index by the Reporters Without Borders (RSF). Under such oppressive circumstances, this Ordinance will be a death knell for the media. The onus is on the government to show us they are acting in good faith by discarding the proposal to introduce a singular regulatory authority and redirecting its efforts to

S. 40: “Offences and penalties. - (1) Any licensee and registered entity, declaration and NOC holder or person who violates or abets the violation of any of the provision of this Ordinance shall be guilty of offence punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years or with a fine which may extend up to two twenty five million rupees or with both.

(2). Where any licensee and registered entity, declaration NOC holder or person who repeats the violation or abetment, such person shall be guilty of offence punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years or with a fine which may extend to TWO Twenty-five million rupees or with both.

(3) Where the violation, or abetment of the violation of any provision of this Ordinance is made by a person who does not hold a license, or registration certificate, declaration and NOC such violation shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years, or with fine upto two twenty-five Million, or with both, in addition to the confiscation of the equipment used in the commission of the act.

(4) Whosoever damages, removes, tampers with or commits theft of any equipment of a media station, printing press or system, cinema houses licensed by the Authority, including transmitting, broadcasting, uplinking apparatus, receivers, boosters, converters, distributors, antennae, wires, decoders, set-top boxes or multiplexers, servers etc. shall be guilty of an offence punishable with imprisonment which may extend to three years, or with fine upto two twenty five million , or both.”

S. 43: “Offences to be cognizable and compoundable. - The offences under section 41 shall be cognizable and compoundable.”

“61 Journalists Killed in Pakistan,” Committee to Protect Journalists, https://cpj.org/data/killed/asia/pakistan/?status=Killed&motiveConfirmed%5B%5D=Confirmed&type%5B%5D=Journalist&cc_fips%5B%5D=PK&start_year=1992&end_year=2021&group_by=location. “Pakistan: Escalating Attacks on Journalists,” Human Rights Watch, June 3, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/03/pakistan-escalating-attacks-journalists.

“Pakistan: Under the military establishment’s thumb,” 2020 World Press Freedom Index: RSF, https://rsf.org/en/pakistan.

create an enabling environment for the media by investing in infrastructure, media literacy programs and supporting economic models to make independent media sustainable.