September 8, 2021 - Comments Off on Digital and Social Transformations in Pakistan During Covid-19

Digital and Social Transformations in Pakistan During Covid-19

Huma was born and bred in Lahore and is currently studying Public Policy at NYU Abu Dhabi with a focus on gender studies and public health.

Introduction and objectives

At the start of the pandemic, the Digital Rights Foundation conducted a survey on the impact of the Covid-19 crisis in Pakistan. This survey was open from March to June 2020. The purpose of the survey was to assess the impact of increased digitisation across the country in wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and take stock of the digital and social transformations as part of this process. Some baseline indicators that the survey aimed to measure were:

- The access and quality of access respondents had to digital technologies, including but not limited to tech devices such as smartphones, laptops and broadband connections,

- Understanding of online security and privacy among respondents, including concerns surrounding increased surveillance and tracking mechanisms during the pandemic

- Usage patterns for technological devices and social media, before and during the pandemic,

Context

In a joint statement in March 2020, the Digital Rights Foundation and BoloBhi expressed the digital gap during the COVID-19 pandemic would exacerbate inequalities and social cleavages. According to the statement, “Internet access in Pakistan stands at around 35 percent, with 78 million broadband and 76 million mobile internet (3/4G) connections.”

According to the Inclusive Internet Index 2021, Pakistan fell into the last quartile of index countries, ranking 90 out of a 100; particularly low on indicators pertaining to affordability, from ranking 76 in 2019, just before the pandemic.

Furthermore, the statement also explained that mobile internet (often the most affordable mode of access) has been shut down in parts of Balochistan and ex-FATA due to generalised security reasons. Even for areas that do have access, internet speed varies based on one’s location. For instance, internet speed in Gilgit-Baltistan is significantly slower than internet speed in urban centers of Punjab and Sindh.

Lastly, the statement also expressed concerns that “lower-income families either do not own digital devices or they are shared by the entire family unit; this means that families with more than one member working from home or students with online classes will be forced to make a choice.”

Methodological Limitations

In light of these, certain limitations of the survey results need to be addressed. Firstly, as the survey was disseminated primarily online, through social media channels, messaging apps, and email, basic access to internet and wifi became a prerequisite for respondents. This left out a large majority of the population that have little to no access to the internet.

Secondly, the dissemination methods also reflect a certain cross section of the population who regularly use and access social media channels of their own accord, since this was the primary means of distribution.

Lastly, this survey was conducted in English and therefore respondents were limited to those who could understand and communicate in English particularly.

Demographic Summary

The geographic distribution of the respondents reflects the pattern of accessibility and digital connectivity expressed by the statement. Inhabitants of Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad and Faisalabad formed the majority of the respondents, with 48, 27, 24 and 11 responses from each city respectively. In total, there were 4 responses from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 1 from Balochistan and none from Gilgit Baltistan.

We received a total of 128 responses to the survey. 71 (55%) respondents identified as females, 54 (41.9%) as males, with 1 gender non-binary individual and 2 respondents preferring not to disclose their gender.

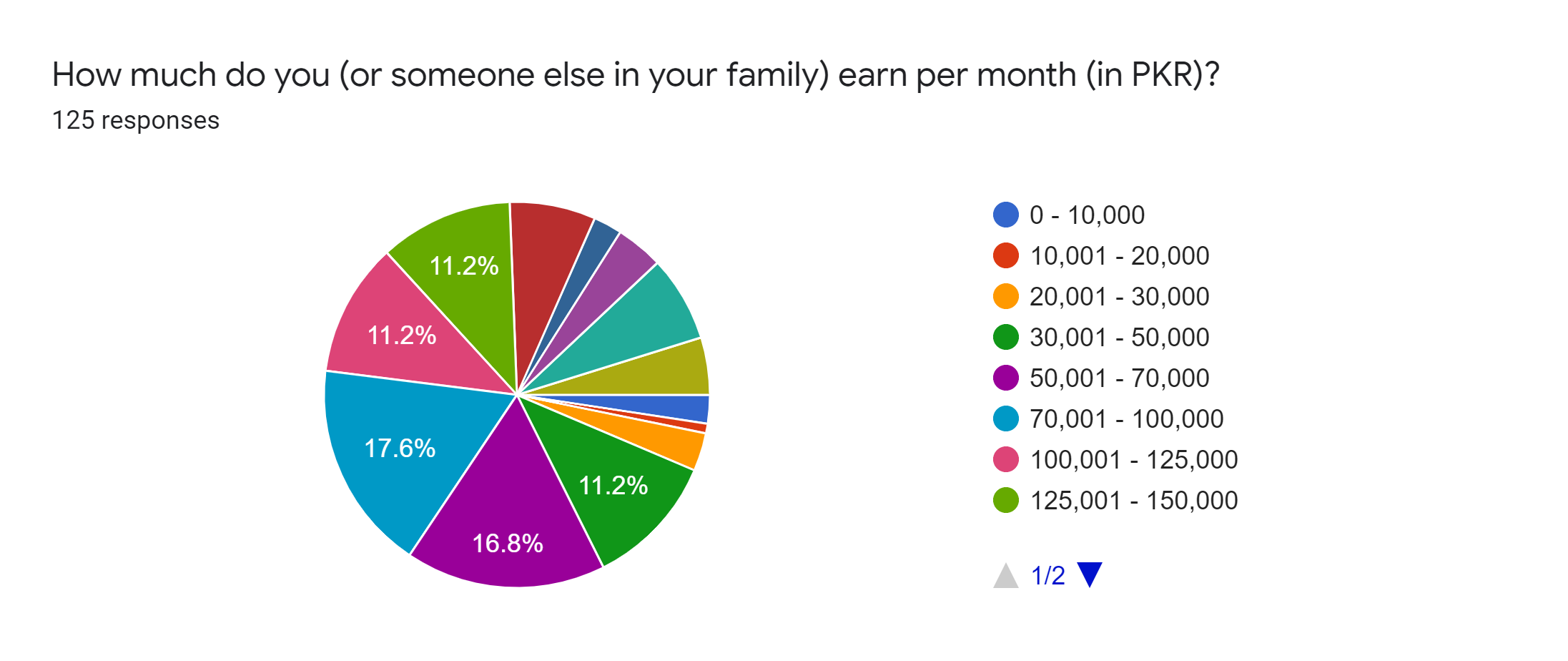

53% of the respondents were between 25-34 years old, with those between 18 - 24 years and 35 - 44 years old forming the next biggest age brackets of respondents (20.3% and 19.5%, respectively). The large majority of our respondents were therefore employed on salary, self-employed or students. As shown below, while a diverse range of incomes were reported, most respondents fell in the middle to upper income brackets.

Survey Results: Major Takeaways

Digital Divide

93.8% of the respondents reported having access to a broadband connection. The eight respondents that do not have access to a broadband connection, all reported using 3G or 4G services.

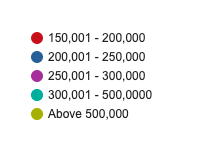

Nearly all respondents reported having access to 3G and 4G services; however the amount that respondents spent on these services varied widely, as shown in the graph below:

Despite the reported distribution of access to broadband connections and 3G/4G services, a large majority of the respondents reported difficulties and obstacles in connectivity.

55.7% of the respondents reported experiencing weak or no broadband connection once a week. 15.6% of the respondents reported experiencing weak connections once a month, while the rest experienced these not very often or not at all.

54% of respondents felt that a lack of internet infrastructure in their area impacted their ability to participate in class or at work negatively during Covid-19; of these 45.2% of the respondents reported inconsistent connectivity as the main reason.

59.8% of the respondents felt that internet speed, in particular, negatively affected their experience. Of these, 34% felt that the internet speed had actually decreased in their area in the previous one month at the time of the survey.

Nearly 80% of the respondents agreed that the internet should be a public utility during a crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic. 9.4% of the participants argued that while it should be subsidized, it shouldn’t be free.

While by number, the majority (38.9%) of respondents reported that issues faced in accessibility, connectivity and quality did not negatively impact their access to job opportunities or education, it is important to note that nearly all respondents from outside of Lahore, Islamabad, Karachi and Faisalabad felt that it did. This points to a geographic disparity in access, connectivity and digitisation. Due to the over representation of respondents from more urbanised and digitalised areas of the country, the results of the survey are somewhat skewed.

A Dawn article published in June, 2021 describes the gendered disparities in access to digital technologies: there is a 38 percent gender gap in mobile phone ownership (the highest in South Asia) and a 49 percent gender gap in internet usage. Our study however did not reflect the same disparities, with respondents of all genders self-reporting similar access to technologies, ownership of gadgets, internet usage, and privacy too. This difference owes itself largely to the demographic, especially class, particularities of this study’s respondents.

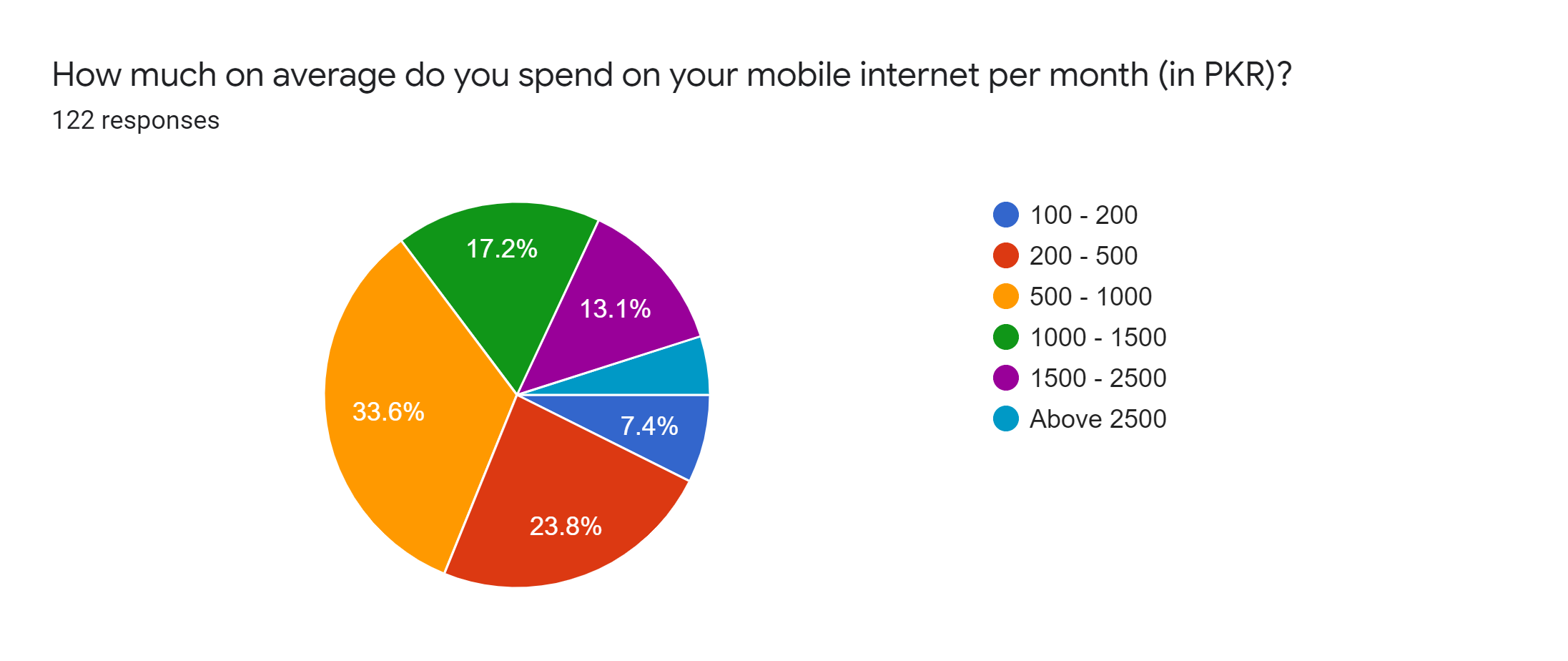

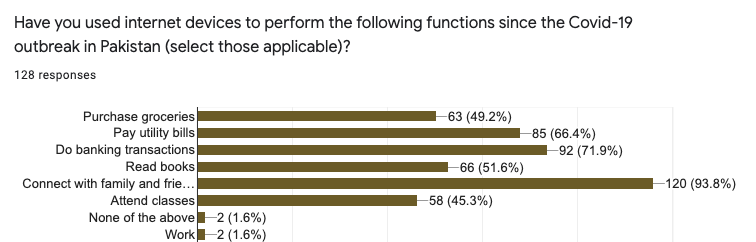

Nearly 73% of the respondents started working from home completely or at least partially after the advent of the pandemic, the following transformations were also reported in terms of increasing technological devices and internet usage. While this points towards an increasing digitisation of Pakistan, as more and more online services are utilised for what would previously be performed through non-tech means, much of the spread of digital technology - especially those indicated here - are limited to urban areas. For example: Airlift Express, one of Pakistan’s online delivery startups, delivers its services in Karachi, Lahore, Faisalabad, Gujranwala, Sialkot, Islamabad, Rawalpindi and Peshawar. This certainly reflects the demand patterns across the country, but is also reflective of already present geographical cleavages in digitising basic services.

The options for the above two questions were: Purchase groceries Pay utility bills Do banking transactions Read books Connect with family and friends Work Attend classes

The variance between the increasing usage of online services compared to the disparity in the provision of these services is reflected tremendously in the increasing demand for quality internet in all areas that were essentially not urbanised cities. Particularly, earlier in the year, students, activists and residents demanded better internet connectivity for Gilgit Baltistan, especially with an influx of students looking to attend online classes after returning due to the pandemic. In an article published in The Diplomat, student activists demanded better internet services in the Balochistan province too, a demand that was met with repression and arrests on the part of the authorities.

Privacy

With the advent of the pandemic, governments globally introduced a range of new policies to control and inhibit the spread of the virus within local populations. Among these were various surveillance methodologies employed to trace contacts of infected individuals as well as control compliance with other policies. Various organisations and human rights monitors have protested against the unregulated use of these extraordinary measures and strategies under the banner of public health measures, arguing that these infringe upon civil rights, especially the right to privacy, and by extension democracy itself. For example, Privacy International argued: “Unprecedented levels of surveillance, data exploitation, and misinformation are being tested across the world.”

In particular, a report dated June 2020 highlights the vulnerabilities of Pakistan’s tracking system executed through a COVID app, it was noted that “the app uses hard-coded credentials, which it sends insecurely, to communicate with the government server, and it downloads the exact coordinates of infected people in order to provide a map of their locations. A second independent test found that the app uses an unencrypted database that can be accessed by either an attacker with physical access to the device or a malicious app with root access.”

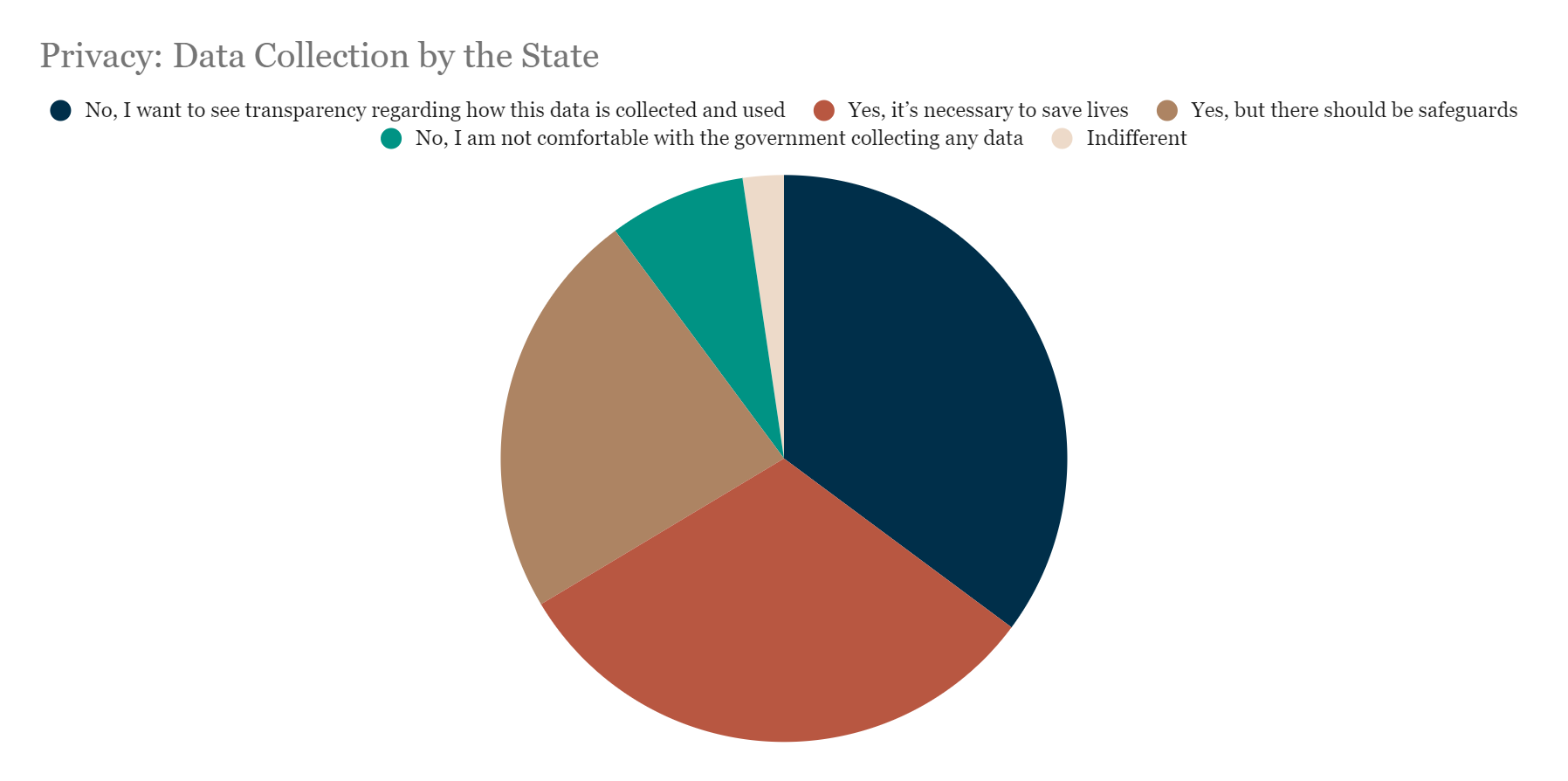

The response to these mechanisms was varied in the survey results. 43% of the respondents expressed similar concerns over the government’s increased use of tracking and data collection mechanisms to record patients' health, travel and contact histories, with around 35% arguing that they wanted to see more transparency with the data collection processes. 23.4% of the respondents were comfortable with their data being collected but with the condition of some safeguards being present. Lastly, 31.3% agreed that this data collection was essential and were comfortable with it in its current form.

However, a large majority of respondents (nearly 55%) were not comfortable downloading a contact-tracing application on their phone, compared to the 34% who were. The rest were indifferent. This ratio increased when we asked if they would be comfortable if they government mandated said applications - 64% responded that they wouldn’t, while only 27% responded affirmatively.

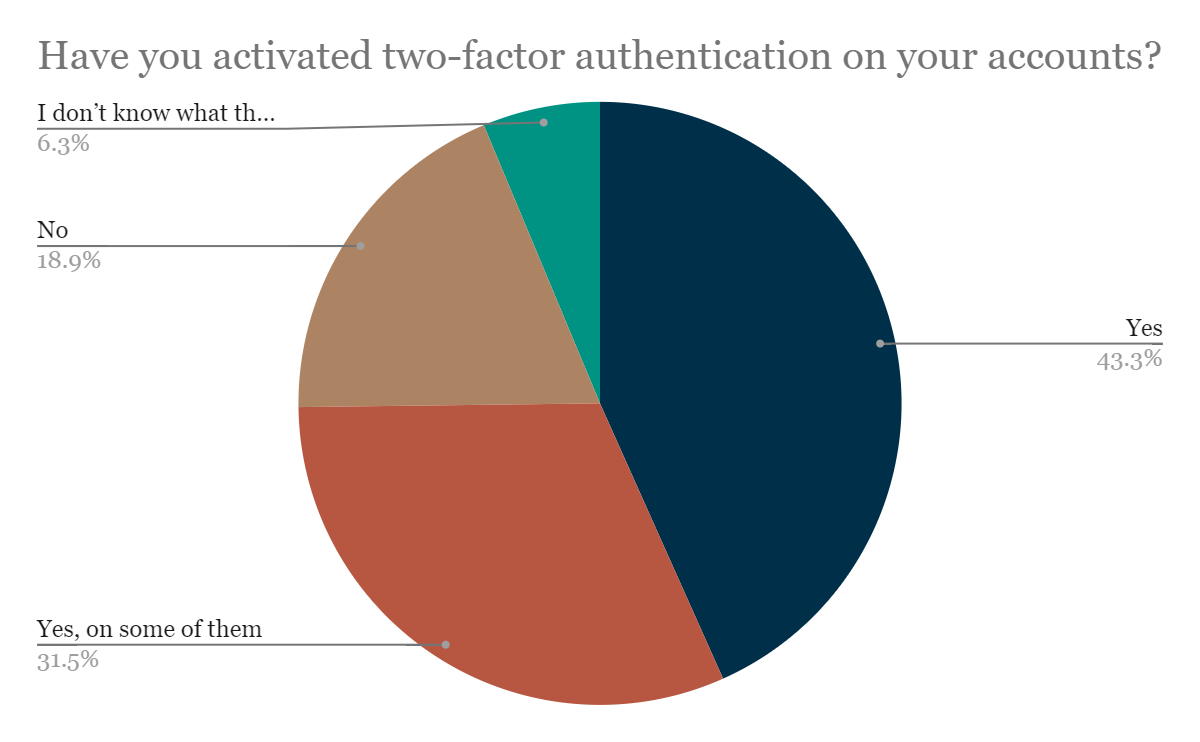

All that said, our respondents did report having access to and knowledge of digital safety and security - for example, as shown in the graph below, a significant majority reported using two factor authentication. Similarly, upto 93% reported that some or all of their devices were password protected.

Lack of information, Misinformation and Fake News

According to a report published by the Digital Rights Monitor, “even as the internet use soared across the country during the pandemic, people in the newly merged districts continued to rely on printed brochures and radio to get information about the virus. The delayed information about COVID-19 could have been fatal for those who would have contracted it, and lack of information about it would have promoted its spread as well. Not only were people barred from accessing crucial life-saving information, now their routine access to healthcare was also restricted.”

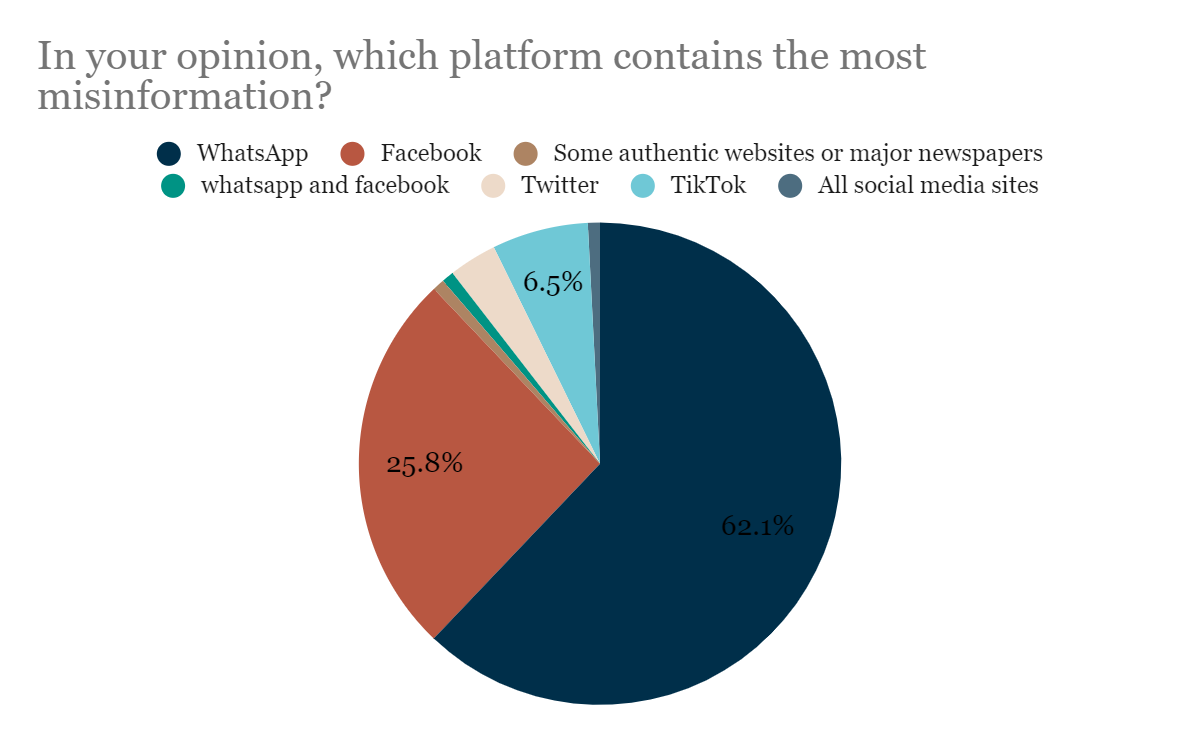

Furthermore, the ‘Manual on Fake News during COVID-19’ written by Digital Rights Foundation argued that fake news, especially on Whatsapp, was at an all time high since March 2020. The kinds of misinformation included: fake cures to mitigate the spread of the virus and manage illness, misinformation about the vaccine and it’s efficiency and so on.

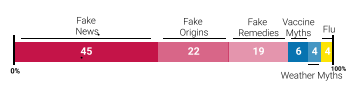

In a study published in 2020 about Covid-19 related Whatsapp messages, Javed et al. used the following illustration to categorize misinformation about the pandemic. Fake news formed the largest of these, including wrongly identifying people diagnosed positive, the amount of deaths globally, hysteria-inducing news about surveillance systems and data collection.

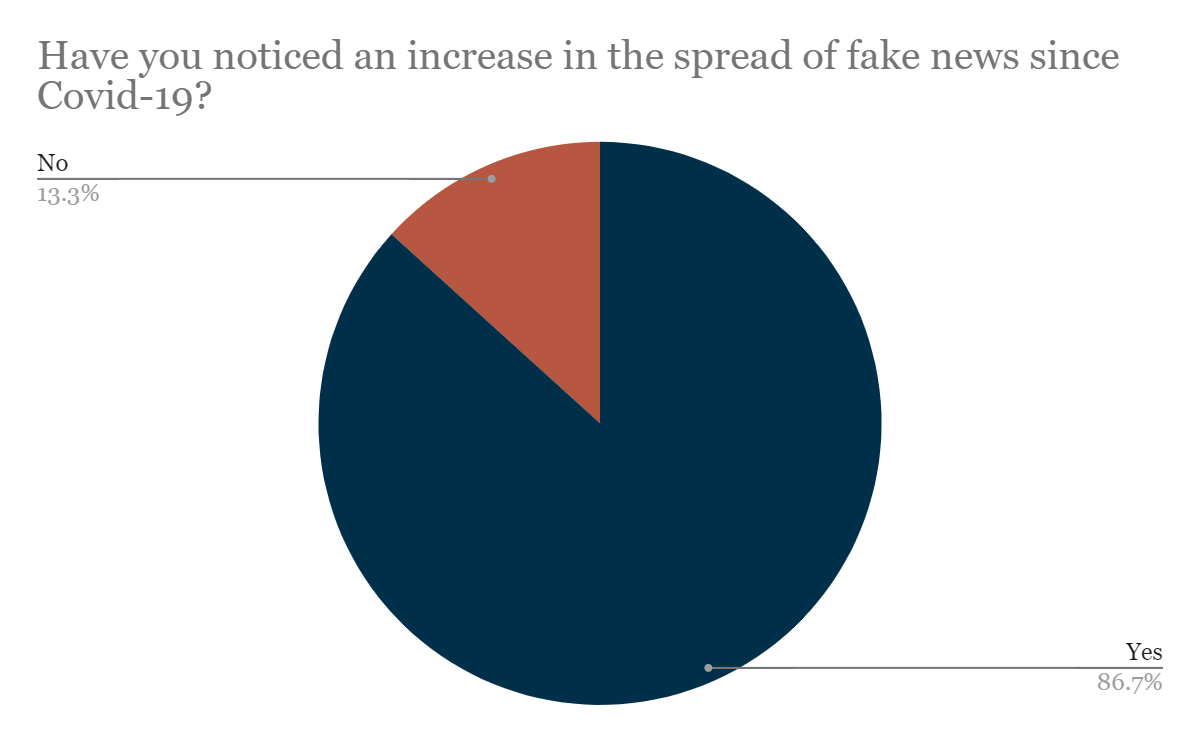

As the graph below shows, a large majority of respondents to DRF’s survey felt that fake news has increased during the pandemic.

Furthermore, a large number of respondents felt that Whatsapp contained the most misinformation amongst major social media platforms. 95% of respondents reported that they verify information before sharing it further on social media, especially Whatsapp.

According to these initial survey results, Covid-19 related digital transformations, privacy and state facilitated data collection and the effects of varied access to digital technologies is differently perceived across respondents. While they provide baseline data for further study and research, some important caveats to digital research remain, especially driven by huge disparities in access to the internet and other related devices. Further research may relate to studying disparities relating to gender, income level and so on.

Bibliography:

-

Javed, R., et al. A First Look at COVID-19 Messages on WhatsApp in Pakistan. , arxiv.org/pdf/2011.09145.pdf.

-

World Health Organization: WHO. “Joint Statement on Data Protection and Privacy in the COVID-19 Response.” Who.int, World Health Organization: WHO, 19 Nov. 2020, www.who.int/news/item/19-11-2020-joint-statement-on-data-protection-and-privacy-in-the-covid-19-response.

-

Ramsha Jahangir. “Govt’s Covid-19 App Sparks Furore over Security Flaws.” DAWN.COM, DAWN.COM, 11 June 2020, www.dawn.com/news/1562767.

-

“International Growth Centre.” IGC, 6 Apr. 2020, www.theigc.org/blog/covid-19-pakistans-preparations-and-response/.

-

Tribune. “Did WhatsApp Fail Us during the Pandemic?” The Express Tribune, Tribune, 8 Mar. 2021, tribune.com.pk/story/2288152/did-whatsapp-fail-us-during-the-pandemic.

-

“The Covid Conspiracy: Misinformation in Pakistan during COVID-19.” Friedrich Naumann Foundation, 18 Dec. 2020, www.freiheit.org/pakistan/misinformation-pakistan-during-covid-19.

-

Amin, Aliza. “TECHNOLOGY: TOWARDS a REAL DIGITAL PAKISTAN.” DAWN.COM, DAWN.COM, 6 June 2021, www.dawn.com/news/1627705.

-

“Pakistan: Freedom on the Net 2020 Country Report | Freedom House.” Freedom House, 2019, freedomhouse.org/country/pakistan/freedom-net/2020.

-

Shah Meer Baloch. “Pakistan’s Great Digital Divide.” Thediplomat.com, 8 July 2020, thediplomat.com/2020/07/pakistans-great-digital-divide/.

-

Pakistan. “DataReportal – Global Digital Insights.” DataReportal – Global Digital Insights, 11 Feb. 2021, datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-pakistan.

Published by: Digital Rights Foundation in Blog

Comments are closed.