November 11, 2020 - Comments Off on Punjab Police Women Safety App: Old Approach, New Interface

Punjab Police Women Safety App: Old Approach, New Interface

November 11, 2020

This week the Punjab police launched it’s ‘women safety’ android phone application in an effort to leverage technology to enhance policing for women’s safety. After immense and justified backlash in the aftermath of the horrific motorway gang-rape incident in Septemeber, it is not surprising that the Punjab police is attempting to implement women-centric reform. However, as an organisation working on tech and gender for a number of years, the Digital Rights Foundation (DRF) sees the approach and the application both as wholly inadequate for tackling the issue of gender-based violence in the country.

The application can be downloaded from Google Play Store here.

What does it do?

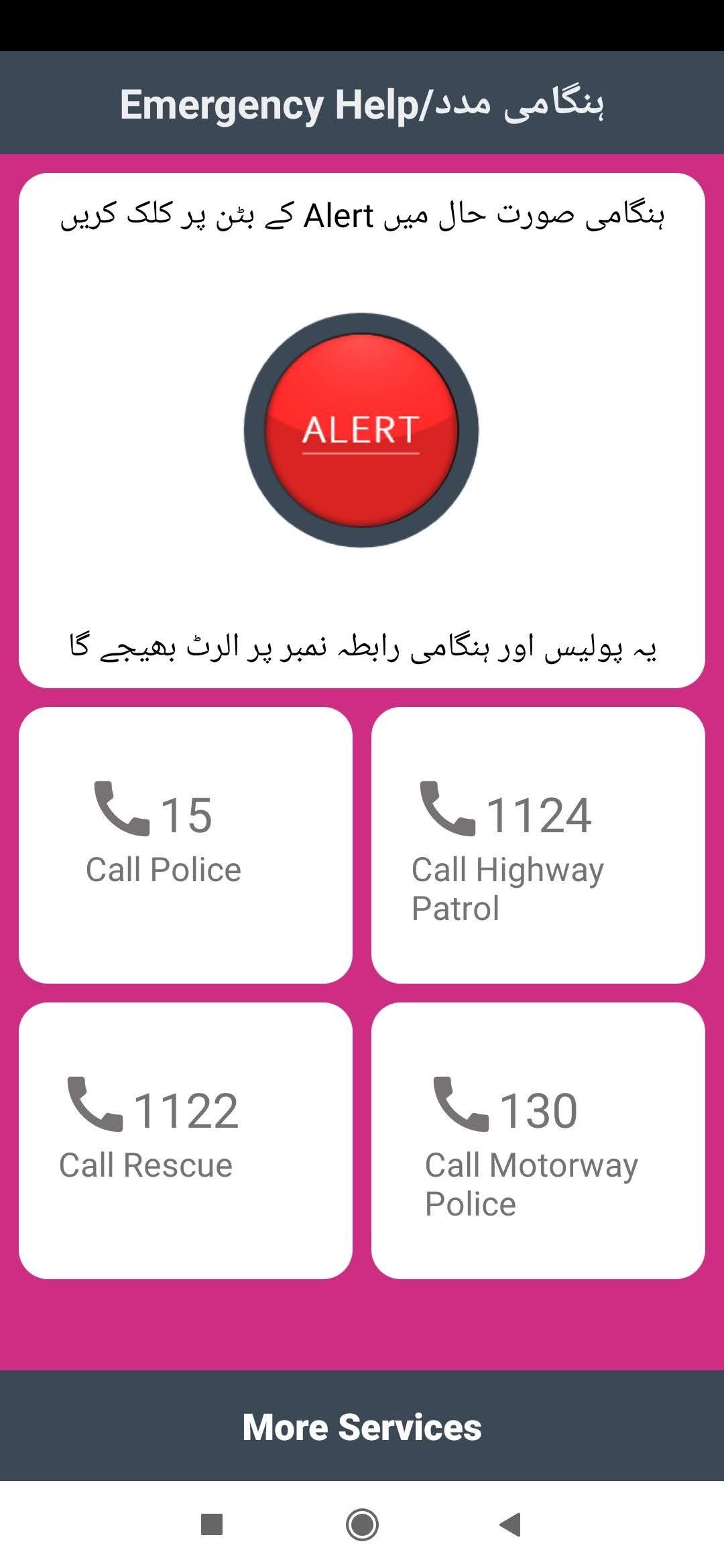

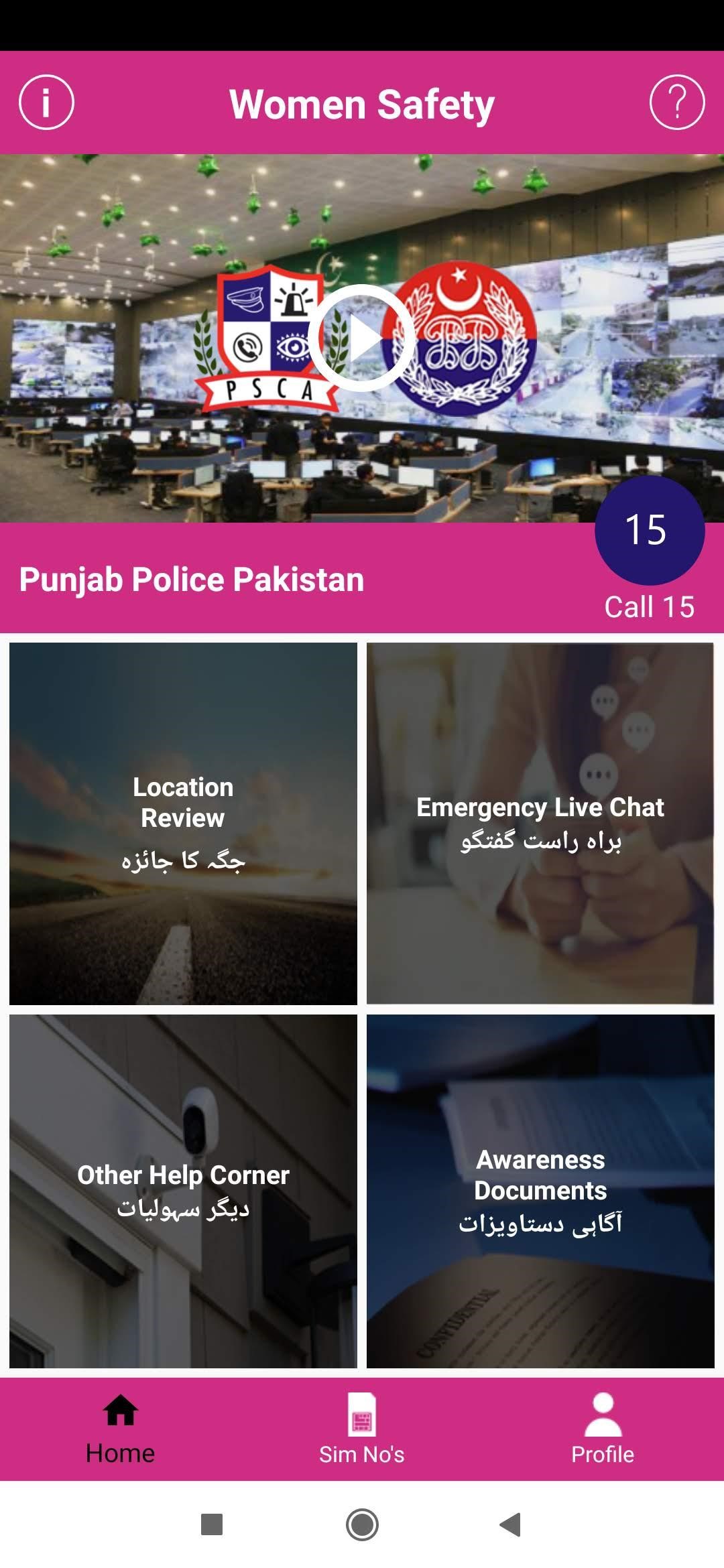

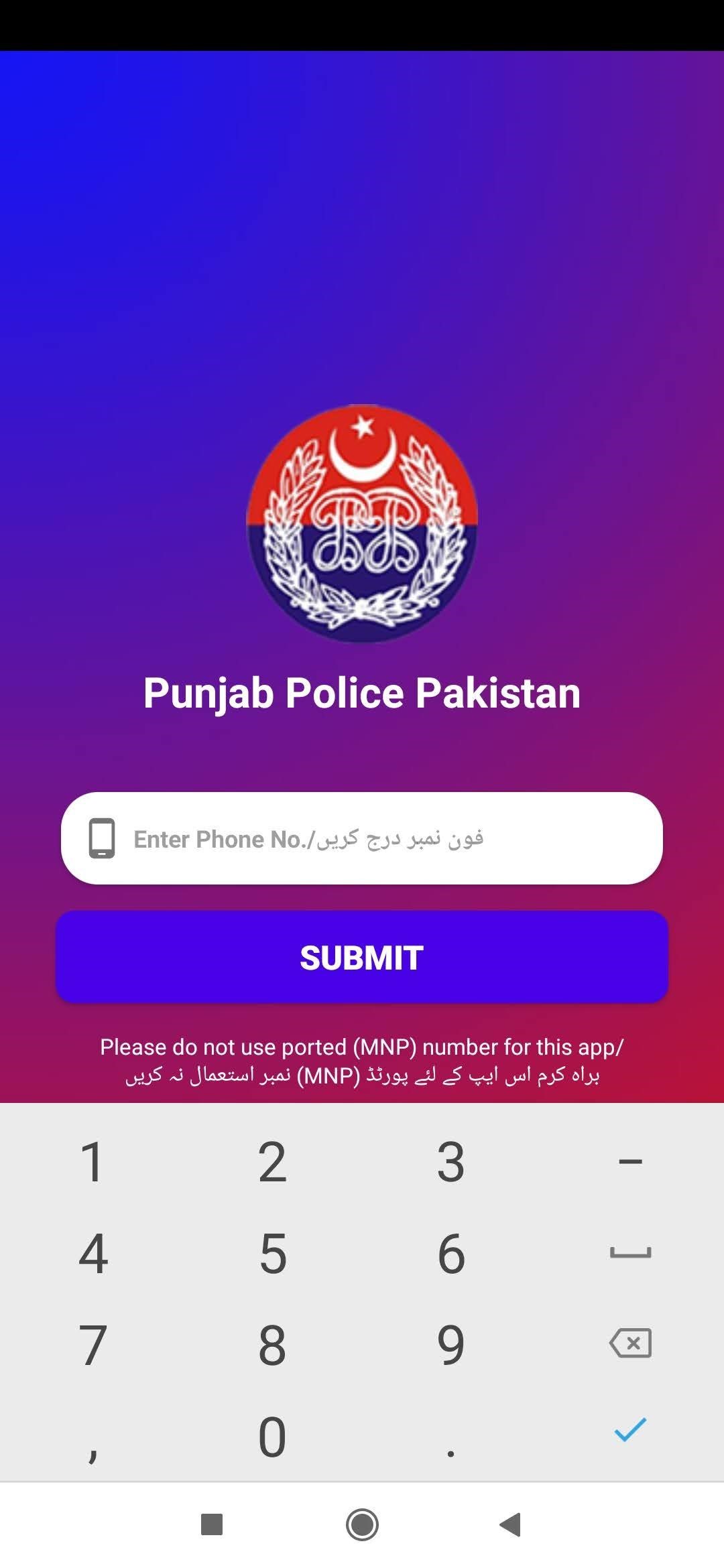

The main feature of the application is its ‘panic button’ which can alert the law enforcement authorities regarding an incident of gender-based violence at a particular location. Apart from that, the application provides access to numbers of the following agencies: Punjab Police Emergency Helpline 15, Rescue 1122, Punjab Highway Patrol and Motorway Police.

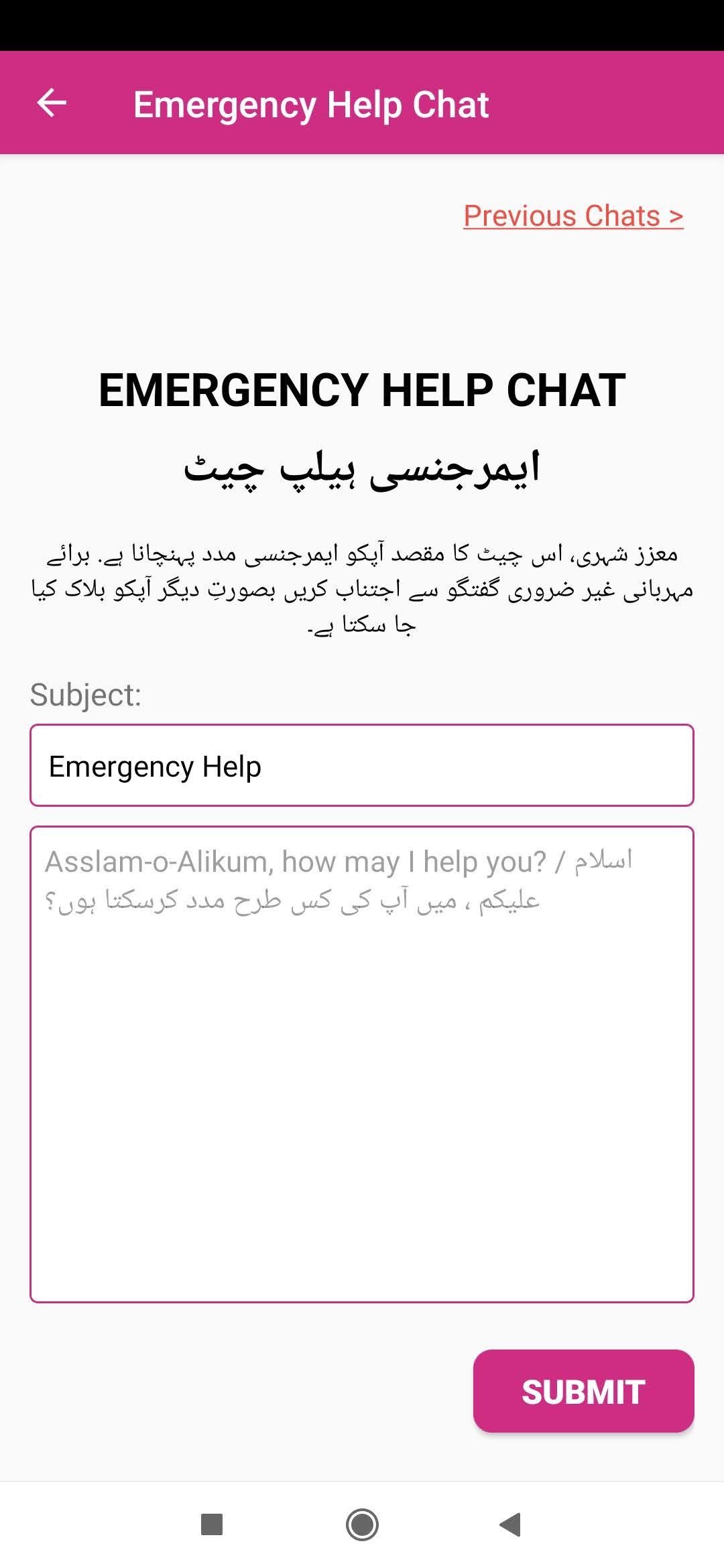

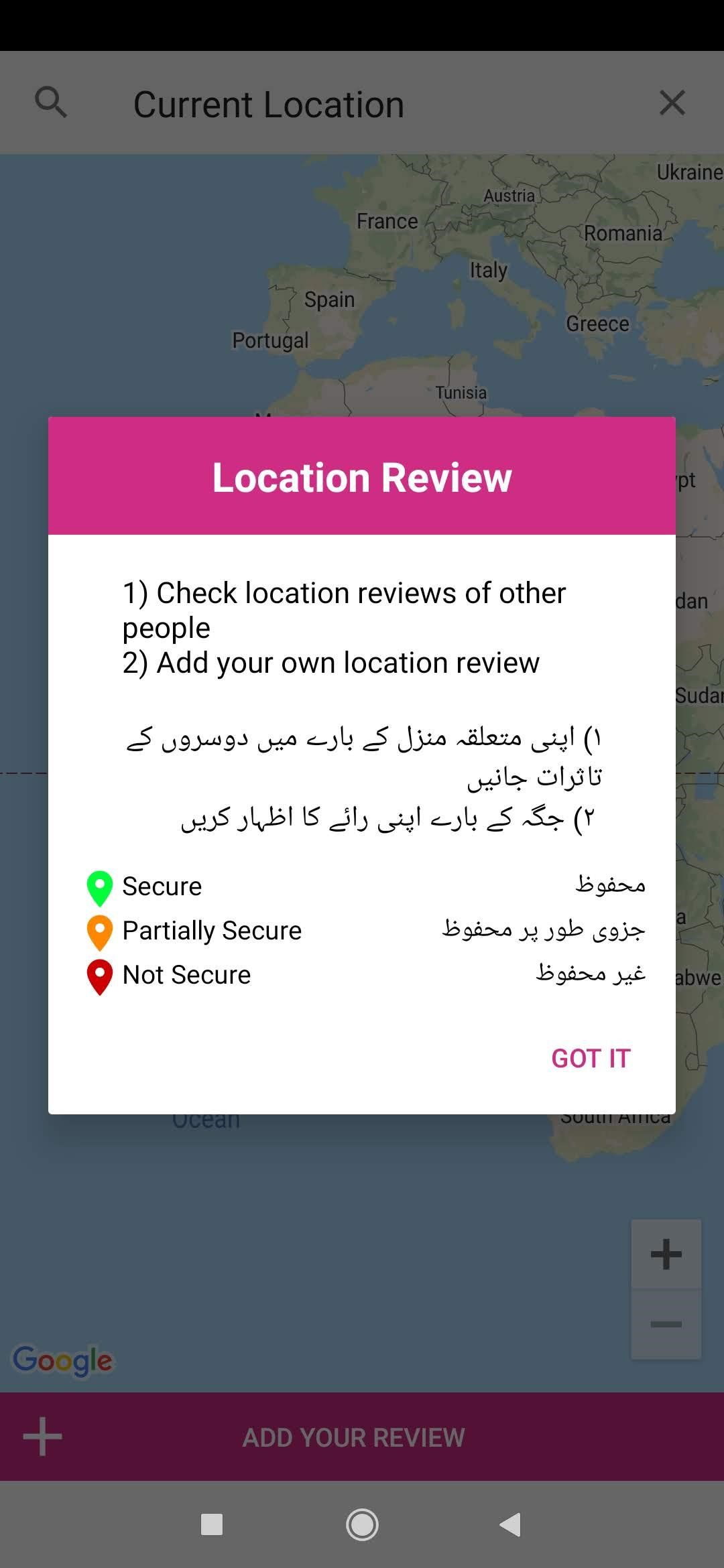

Furthermore, the application has an ‘emergency live chat’ feature, though it is unclear whether the feature is a chatbot or run by the Punjab Police personnel. There is also a section on laws relating to violence and harassment; however, our team felt that the section needed to be translated into Urdu as well and could do with more visual/video-based content to make the laws more accessible. Lastly, the app crowd-sources safety reviews of different locations across the province, allowing users to pin rate locations as “secure”, “partially secure” and “not secure” according to their experience.

The Location Review feature is a good idea as it allows policymakers to track which locations are marked and unsafe and design policy interventions to rectify the problem. This, however, comes with a caveat as the data will only be meaningful if a large number and diverse set of users contribute to it. Additionally, data collected from these reviews should not be used to justify surveillance and over-policing measures in certain locations, which create additional human rights concerns and issues of discrimination rather than solve the problem of women’s safety.

Limitations

Currently, the application is only available on Playstore and compatible with Android phones, which excludes those with iOS-based phones. Furthermore, given that Pakistan has one of the highest gender digital divides in the world, the application essentially only caters to women with smartphones and access to mobile internet. According to the GSMA “Mobile Gender Gap Report 2020”, Pakistan has the widest mobile ownership gender gap as women were 38% less likely than men to own a mobile phone and 49% less likely to use mobile internet. As per a study by LirneAsia, a think-tank based in Sri Lanka, Pakistani women are 43% less likely to use the internet than men.

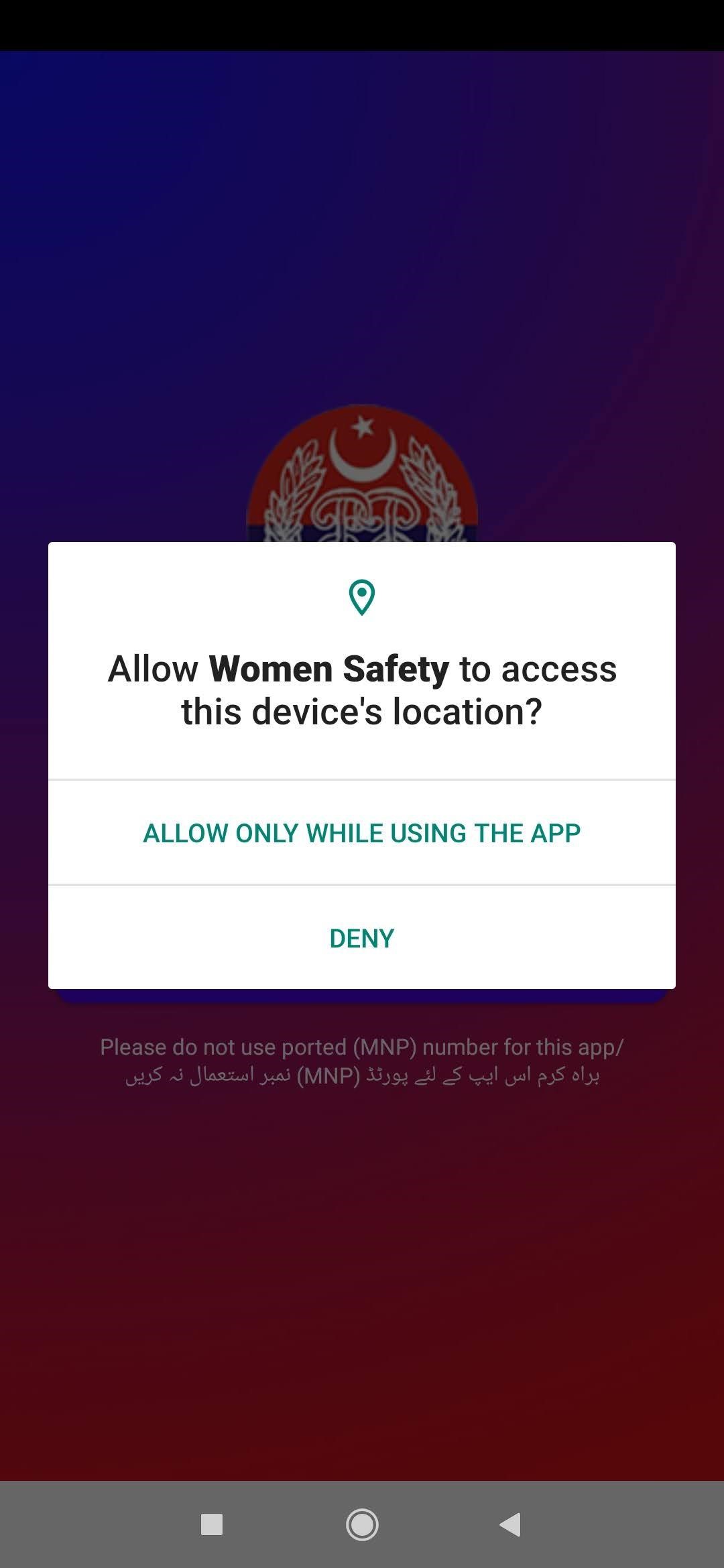

The digital safety team at DRF reviewed the application to find a number of issues in terms of privacy. Given that the app collects highly personal information including phone number, location access and NIC number, robust data security and protection policies must be in place to ensure that the women using the application can trust the technology. Furthermore, the permissions of the app include GPS and network-based location, phone number, access to phone contacts, media files and storage.

The digital safety team at DRF reviewed the application to find a number of issues in terms of privacy. Given that the app collects highly personal information including phone number, location access and NIC number, robust data security and protection policies must be in place to ensure that the women using the application can trust the technology. Furthermore, the permissions of the app include GPS and network-based location, phone number, access to phone contacts, media files and storage.

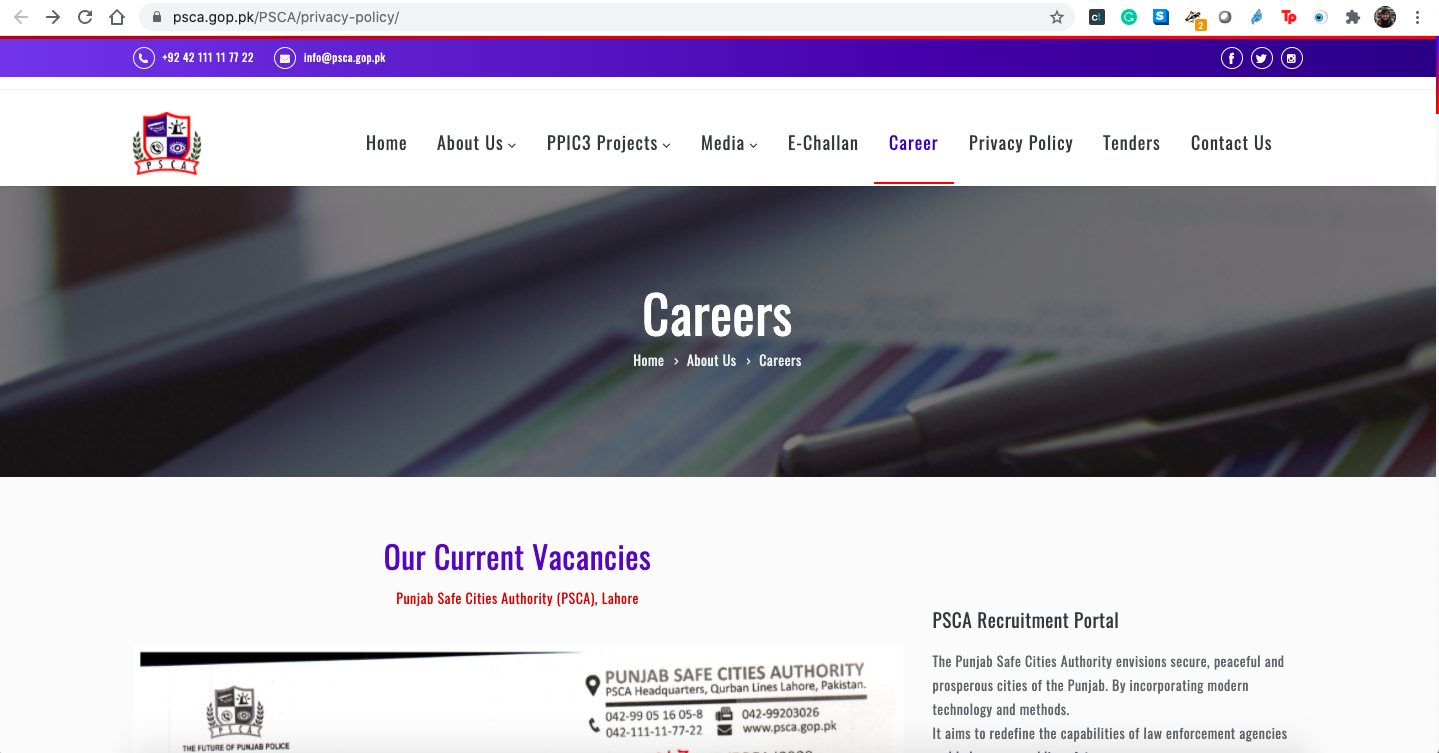

Unfortunately, when the team tried to review the privacy policies in place, the link redirected to the ‘Career page’ on the PSCA website, https://psca.gop.pk/PSCA/privacy-policy/:

For anyone using the app, it is apparent that women’s privacy and safety of their personal information was not a priority for the Punjab Police or the developers of this app. For many women reporting a crime of gender-based violence is accompanied by immense anxiety about privacy in terms of their identity and information--without these assurances, women are unlikely to place their trust in the app. In the absence of personal data protection legislation in the country, lack of privacy policies and protocols is a huge concern. Any intervention for women’s safety that neglects to keep their private data safe is counterproductive and wholly incomplete.

Technology as a Silver Bullet for Women’s Safety?

This is not the first time that authorities and tech developers across the world have sought to introduce applications that can address the issue of gender and sexual violence. In fact, this is not even the first time the Punjab government has attempted this, as the current application seems to be a relaunch of an old application developed by the Punjab Safe Cities Authority (PSCA) introduced in 2017. Nevertheless, there is increasing consensus within researchers and experts that women’s safety applications are unsuited to adequately addressing the question of violence against women.

Firstly, these applications treat women’s safety as an issue that only occurs in public places and crimes perpetrated by strangers. This approach fundamentally misunderstands issues of violence, which are perpetrated inside the home (domestic violence, marital rape and sexual violence at the hands of family members and ‘trusted’ individuals). This means that applications such as these are only scratching the surface of the violence and harassment that women face in society at large.

Secondly, no amount of technology and applications can solve the systemic problems of misogyny and patriarchal mindsets within the police and public institutions. Often women do not report cases of violence because of societal perceptions around victims and victim-blaming by law enforcement bodies. Technology will not change these attitudes. Applications such as these just provide a new interface for an old institution. Until and unless law enforcement bodies and the legal system, in general, engage in systemic reform at every level, any technological interventions will be rendered superfluous.

Thirdly, surveillance cannot and should not be posited as a solution to women’s safety. DRF has pointed out several times that technological interventions that seek to increase surveillance of women’s movement and bodies in order to ‘protect’ them are simply benevolent and paternalistic patriarchal control in another name. Technology often ends up replicating familial and societal surveillance of women’s bodies which does not truly emancipate or change the root causes of the violence against them.

Fourthly, if the app seeks to serve all women it should take into account issues of accessibility for women and persons with disabilities. Currently, for instance, the app lacks features to make the text and graphics readable for visually impaired persons. The app does come with a video explaining how to use it, however more visual and video content regarding the laws and other features will make it more accessible to women who are not literate.

This application comes less than two months after the motorway incident which shook the mainstream national consciousness on the issue of gender-based violence, particularly rape. It is no secret that the Punjab Police received immense criticism because of the victim-blaming remarks of the CCPO Lahore, Umar Sheikh. As per data collected by the DRF team, through monitoring of English-language newspapers, 123 cases of gender-based violence have been reported in just two months after the incident. Incidents such as these often compel law enforcement to engage in interventions and reform that creates the public perception that steps are being taken to address the problem--however cosmetic changes such as new apps do little to actually change things. ‘Internet Democracy,’ an organisation based in India, has noted that after the 2012 Delhi rape case several ‘women’s safety’ applications emerged. Similar to Pakistan, these technological interventions did little to change the ground realities that women face on a daily basis.

Conclusion

It seems that the Punjab Police has taken a top-down approach to women’s safety by developing (or rather rebranding) technology to ‘protect’ women without taking into account the actual lived experience of women and gender minorities in Pakistan. No effort seems to have been made to consult women’s rights and digital rights organisations when making the technology. Technology cannot be expected to enact social change or facilitate marginalised communities if its design does not incorporate the very communities that it seeks to serve. Additionally, technology cannot be used as a smokescreen to dent criticism of policing and the barriers women face at the hands of law enforcement if it is not accompanied by structural and meaningful reform.

Published by: Digital Rights Foundation in Blog

Comments are closed.