Earlier last week, senior journalist Munizae Jahangir became the target of threats and intimidation as a consequence of her reporting on a group involved in making fake blasphemy allegations online. Munizae Jahangir had interviewed the families of victims who were allegedly targeted by the group, for her talk show on Aaj TV.

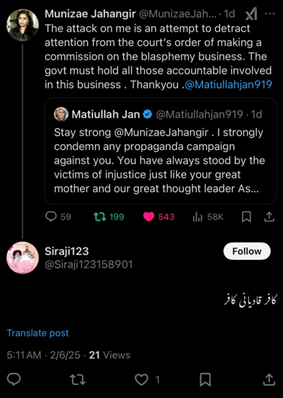

The group, whose actions and campaigns have been termed “blasphemy business”, allegedly entraps young people, coercing them to commit blasphemy, and then extorting money from them by threatening them with blasphemy allegations. Pakistan’s Islamabad High Court has also proposed the formation of a government commission to investigate such cases of entrapment that occur through false blasphemy allegations. According to a statement by the HRCP, which Jahangir co-chairs, the threats hurled at her are a deliberate deflection of attention by participants of the “blasphemy business” away from the Islamabad High Court’s proposal.

Being accused of blasphemy whilst working in the public eye brings with it a heightened sense of danger. In Pakistan, allegations of blasphemy have resulted in numerous physical attacks in the past - in terms of collective mob violence or otherwise - sometimes with fatal consequences, such as the assassination of the former Governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer by one of his bodyguards in 2011.

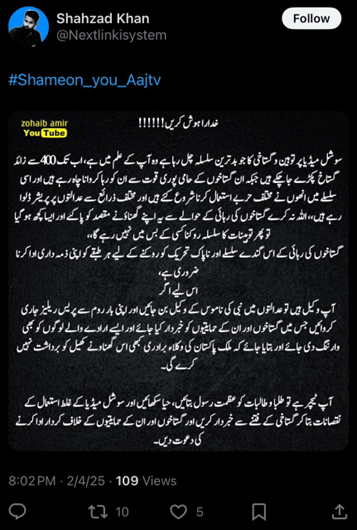

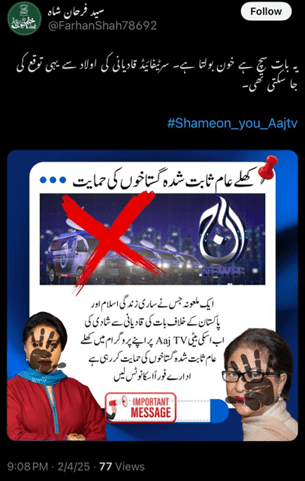

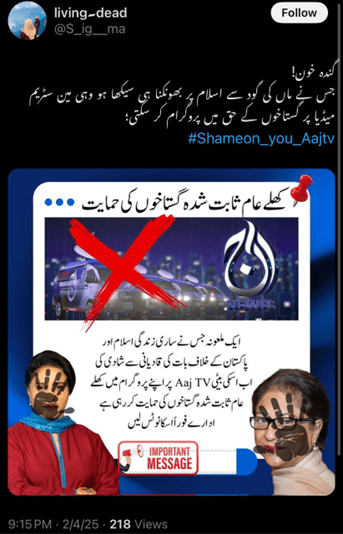

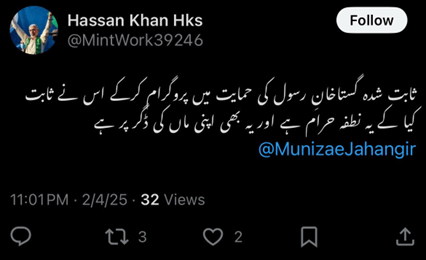

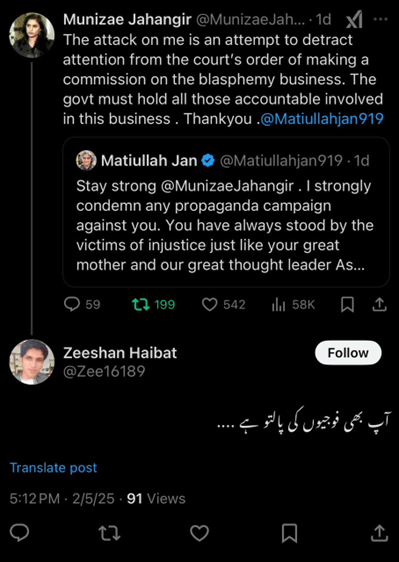

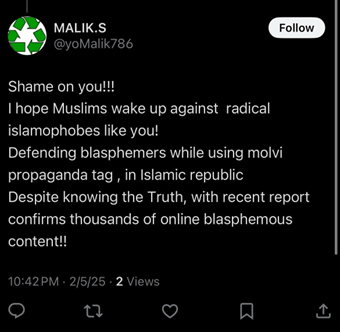

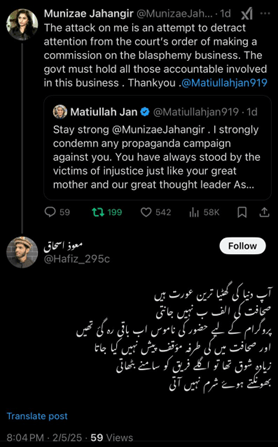

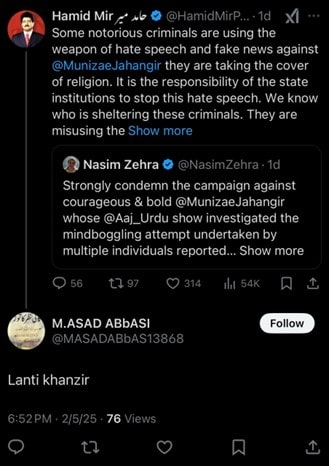

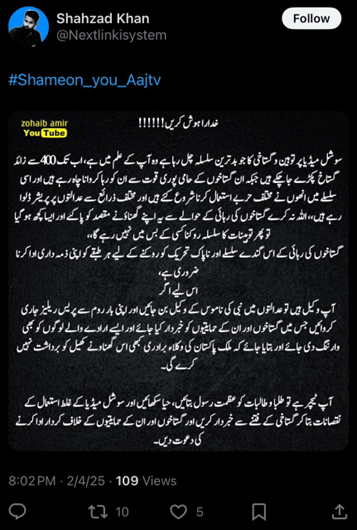

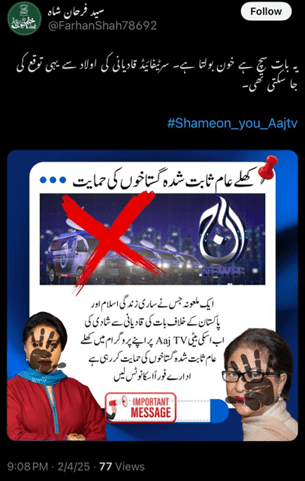

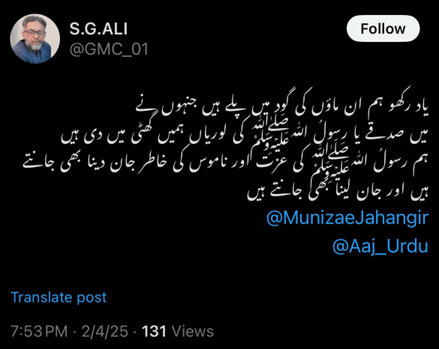

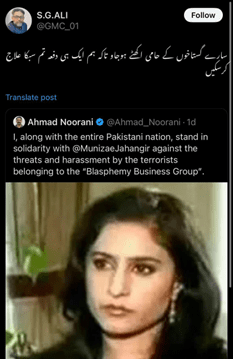

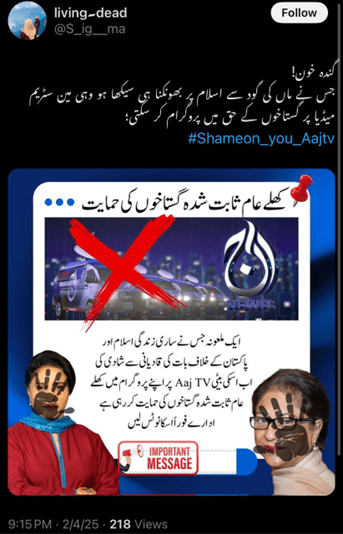

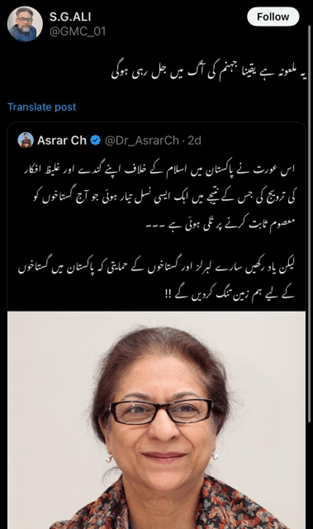

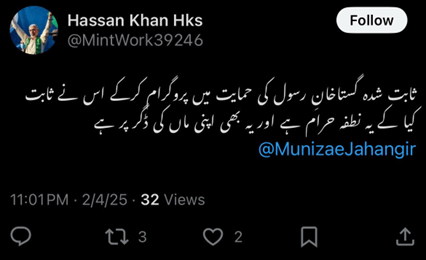

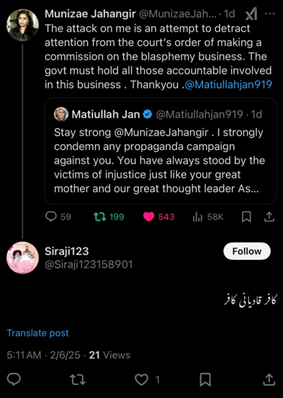

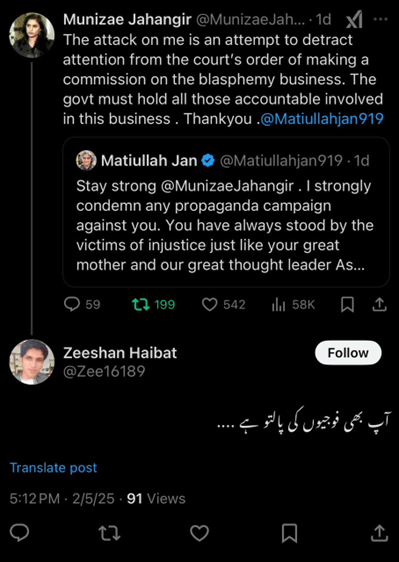

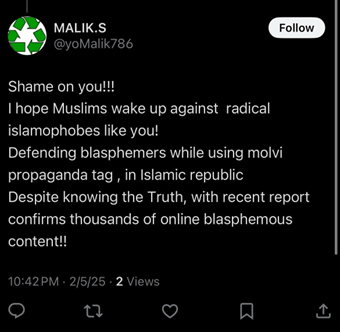

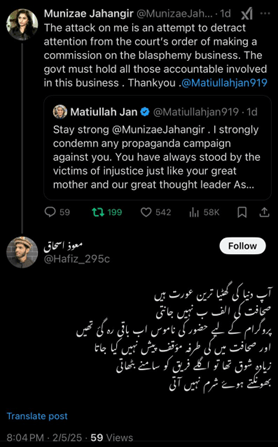

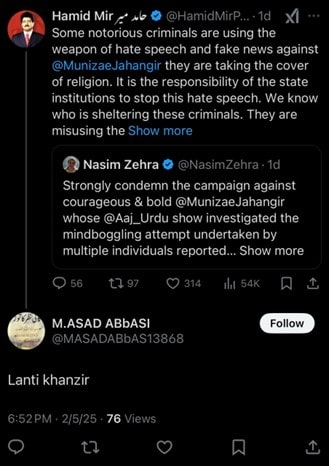

DRF investigated 50 posts by at least 15 users on the X (formerly Twitter) social media platform and discovered instances of hate speech perpetrated against Munizae Jahangir in this case, which comprised evidence of a planned, targeted campaign. These include calling for a boycott of her talk show, issuing indirect death threats against her, and accusing her of committing blasphemy herself.

Under Section 10B of the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016, hate speech has been made a punishable offence. It notes:

Whoever prepares or disseminates information through any information system or device that advances or is likely to advance inter-faith, sectarian or racial hatred, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to seven years or with a fine or with both.

As of the time of this report, a week after originally posting, none of the posts attached have been taken down by X, despite containing explicit threats of harm and numerous users reporting said posts - showcasing a particularly harrowing example of platform accountability failure with potentially dangerous real-world ramifications.

Some of the death threats are documented below, which include allusions to the killing of Salman Taseer (referred to as “Shaytaan Taseer” in one post) for opposing Pakistan’s blasphemy law, and how Jahangir might face a similar fate.

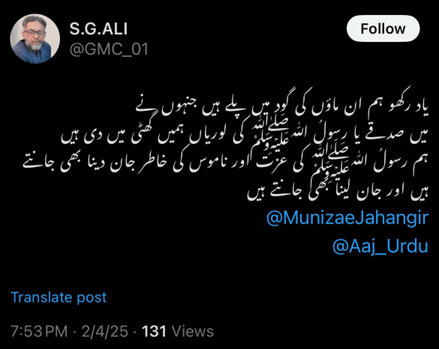

Below are some of the more severe threats and warnings which have been documented, including warnings for Jahangir to “stay in her limits”, with the instigators claiming that they were “ready to sacrifice anything for the sake of the Prophet”. Women journalists are already a vulnerable group in Pakistan. According to a 2022 report by HRCP, “Women report that online violence has taken a toll on their mental health, making them fear for their physical safety, damaging their reputations and often forcing them to quit working.” The DRF Cyber Harassment Helpline receives complaints from across Pakistan related to technology-facilitated gender-based violence and online violence. In 2024 the helpline received 65 complaints from women journalists, highlighting the prevalence of the violence faced. This threat to women journalists persists globally. According to a global study on online violence faced by women journalists by UNESCO and the International Center for Journalists, nearly three in four women journalists, a total of 73%, have faced online violence while reporting.

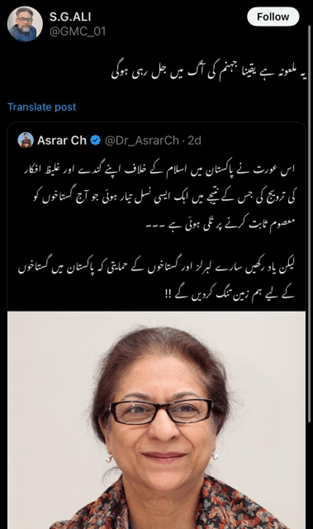

Many of the threats alluded to Munizae Jahangir’s mother, the human rights activist and a former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Asma Jahangir, who passed away in 2018. Posts referred to Asma Jahangir’s activism as “anti-Islamic”, with her death made light of, along with comments that she must be “burning in hell”. The posts also called Munizae Jahangir her “bad blood”, and said that she had been taught to “bark about Islam” in her mother’s lap.

Posts also called Asma and Munizae Jahangir “Qadiyani” and “Qadiyani Kafir” - both being derogatory slurs used to stir up and incite hatred and violence against the Ahmadi community.

DRF also documented explicit calls to cancel Jahangir’s show and threats to boycott Aaj News and to start “trends” against the channel if the channel does not issue an apology, and does not invite those accused of being members of the “blasphemy business” group to express their point of view.

On a separate occasion, Munizae Jahangir was also accused of being a “pet” for the army, of being an Islamophobe, and of spreading one-sided views on her show.

The carefully orchestrated campaign of threats and intimidation gained much traction on X via likes, reposts, and replies of support.

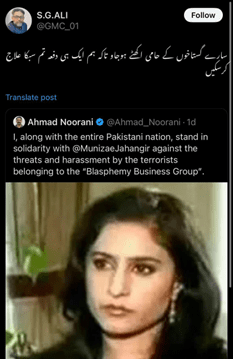

However, DRF also noted that while hate speech, threats, and incitement towards violence was rampant, several journalists including Matiullah Jan, Hamid Mir, Nasim Zehra, Azaz Syed and PTI’s Former Federal Minister for Information Fawad Chaudhry shared messages of support. Some of the journalists that have voiced their support have in turn come under fire for doing so.

Journalist and rights-based collectives such as the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, the Network of Women Journalists for Digital Rights, the Women Journalists Association of Pakistan, The Coalition for Women in Journalism, the Forum for Digital Rights and Democracy (FDRD), the AGHS Legal Aid cell, and the HRCP also issued statements in support of Jahangir.

Nevertheless, the targeted harassment and intimidation campaign against Jahangir for exposing the “blasphemy business” group continues, with little being done by X to curb this orchestrated campaign of hate, despite being in violation of their policies.

X’s Rules on Abuse and Harassment state “You may not target others with abuse or harassment, or encourage other people to do so”. This is the main policy being violated in the campaign against Jahangir. However, the enforcement options for this policy are woefully generic, and inadequate for religiously motivated hate speech of the kind seen in this case. The enforcement options include restricting content visibility and discoverability, requiring post removal in some cases, and suspending accounts “that are dedicated to harassing individuals”. These options allow many cases of abuse and harassment to slip through the cracks because of how generic they are. They fail to take into account the fact that religiously motivated hate speech, which can cost someone their life, is a more serious category of abuse and harassment, and prompt action in cases that involve this category of harassment is particularly necessary. This is unfortunately not the case at present.

Since Elon Musk's takeover, X has disbanded the Trust and Safety teams of the platform, which civil society used to urgently escalate content relating to journalists and activists. The absence of these teams and any official measures on a widely used platform like X is problematic at the very least, as we have seen in the past how hate speech has led to offline violence in countries like Pakistan. X has a responsibility to uphold the safety of its users particularly when they are under attack and there are calls to violence against them.

With documentation such as in this article, and as collected by others, the hope is for the government and platforms to take notice of dangerous patterns and trends especially with regard to sensitive issues in Pakistan such as blasphemy, and for platforms in particular to modify the enforcement of their policies to reflect local contexts.

The topic of blasphemy in general, and particularly speaking out about false blasphemy allegations or expressing discomfort with the existing blasphemy laws in place has always been a trigger point in Pakistan which has led to the loss of livelihoods, homes and lives. This is why this case of religiously motivated hate speech is particularly dangerous.

Platforms such as X need to take into account local contexts and the tremendous pressures of religious extremism in countries like Pakistan while drafting their community guidelines, and take immediate action against orchestrated campaigns such as the current instance. Doing so can proactively aid in nipping the problem in the bud, and prevent such campaigns from gaining widespread social media traction - for it is through the latter that the potential for offline violence can arise, as has been tragically witnessed in the past.

By Sara Imran, Research Associate, Digital Rights Foundation