December 7, 2023 - Comments Off on Beyond the Binary: Expanding the Discourse on Gender-based Violence in Pakistan

Beyond the Binary: Expanding the Discourse on Gender-based Violence in Pakistan

Tehreem Azeem

Faizi was assigned male gender at birth in Toba Tek Singh, Punjab, Pakistan. But over time, her family realized she was not behaving typically for either binary gender. She was a trans person. She spent her whole childhood struggling to understand her own identity while facing harassment from those around her.

Faizi was assigned male gender at birth in Toba Tek Singh, Punjab, Pakistan. But over time, her family realized she was not behaving typically for either binary gender. She was a trans person. She spent her whole childhood struggling to understand her own identity while facing harassment from those around her.

As a child, Faizi underwent the worst forms of violence. When she would go outside of her house, boys would chase and grope her and shout slurs like “hijra.” She would run back to her house as fast as possible.

At family gatherings, she would draw curious stares and roving hands, trying to solve the “mystery” of her body. Her male cousins even hatched plans to see something revealing while swimming together.

Transgender individuals in Pakistan face shocking levels of targeted violence and discrimination rooted in transphobia. Nearly 90% endure some form of physical or sexual abuse in their lifetimes, often at the hands of their own family members. They are often kicked out of their homes for embracing their identities. Many of those go to the nearby transgender community, where they are welcomed warmly. But sadly, the society has not much to offer to them. They are forced to do begging or sex work to earn a living. This frequently leads to further assault. They are murdered brutally by unknowns. They face public harassment in routine. They are raped at private parties where they are invited to perform. This violence persists due to societal prejudice around gender and lack of legal protections for marginalized groups.

Figuring out the societal behaviour

Even at a young age, Faizi understood the treatment she endured from elders was wrong. Over time, she realized she had survived multiple forms of violence.

“Children are the easiest victims since they know nothing of the world. The violence in my life began in childhood. Ours is a male-dominated society where men consider harassment of women their right. I endured even more because of my then-unknown gender identity, though they sensed it,” she said.

Her School also offered no respite to her. Placed in the boys’ section, Faizi faced relentless torment from male classmates who chased, groped, and assaulted her. They would hurl footballs at her body, strip off her pants, and circle around her while unleashing slurs. Sometimes, they would go after her in the bathroom and forcefully hug her to feel her growing body.

“Our parents do the greatest injustice to us by imposing masculinity on us and then sending us into a male world. It’s like serving predators their preferred feast. Trans youth would be safer if they were raised as girls. It would spare them the pain and misery they face from men,” she reflected.

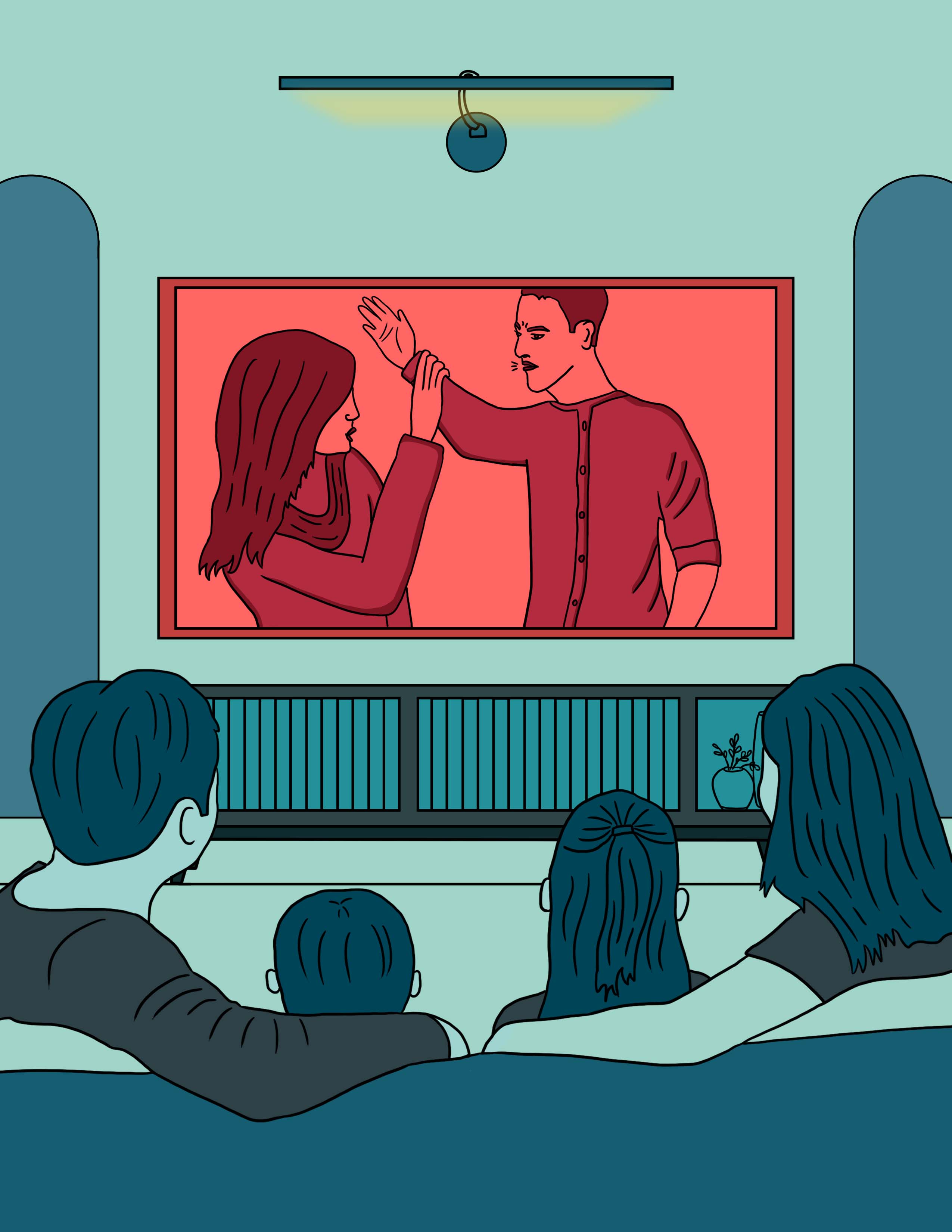

Gender-based violence permeates Pakistan, though it's often narrowly viewed as only impacting cisgender women. In reality, violence extends across genders, afflicting trans people, intersex individuals, non-binary people and more. Women do possess one advantage - societal space to openly discuss their struggles. Organizations fighting for women’s rights in Pakistan can operate visibly, raise voice for them and press the government for protective laws. But for those seen as "lesser" beings pervading social stigma, speaking out proves tremendously difficult. Even young boys and men stay silent, lest they appear "not man enough" to admit vulnerability.

My teachers harassed me

Throughout her education, Faizi endured harassment from teachers seeking to exploit her. In school, the male teachers would call her to the staff room, where they would try to touch her inappropriately. The same pattern continued in college. A teacher openly asked her for sexual favours. Upon refusal, he made college time toughest for Faizi. He did not even allow her to appear in two examinations of intermediate. She later passed the supplementary examinations and went to Faisalabad for an undergraduate degree at Government College University Faisalabad.

The first challenge she faced there was getting a hostel room at the university. The hostel administration did not know where to send her, either to the women’s hostel or to the men’s hostel. They kept sending her from one place to another till she got tired and sat outside in the rain with her luggage.

“When I arrived that night, they shuffled me back and forth between the boys’ and girls’ hostels. I ended up sitting outside in the rain with my luggage. In the morning, I approached the Vice Chancellor and gave him an application to allot me a hostel at the campus. He was kind. He took immediate action and allotted me a VIP room. He also waived off hostel expenses for me. He also told the cafeteria not to charge me for food and drinks during my stay at the university,” she recalled.

I was disowned because of my gender

Faizi’s family asked her to leave the house when she was just thirteen years old. She still remembers the day. Talking about it, she said that day, a group of transgenders had come to our area to celebrate the birth of a boy. Like everyone, she also went out of the house. One of the transgenders recognized her. She gave her a note with her address and some money. Faizi was confused, but the transgender knew what was coming her way.

“She said that a time will come when your family forces you to leave your house. They would not keep you. That time, don't go anywhere, just come to this address. I thought she was crazy. I was settled in my own world. That was my family and my house. Why would they kick me out of the house? But it happened the same evening,” she said.

In the evening, a neighbour complained to her family that they had seen her talking to the transgenders. Her family got angry. The boys were already after her. The relatives and others were also mocking her family. They told her to leave the house, and she left.

She went to that address where she was received happily. Her guru was extremely kind to her. She helped her complete her education. After completing her undergraduate, she went to Islamabad to do her MPhil in Urdu from Allama Iqbal Open University. Once again, she had to figure out a place for her living. She posted about the struggle on her Facebook. The post went viral and reached a woman who was doing a Ph.D. at the same university. She contacted her and told her to come to her house instead of wasting time hunting for a safe place. She went to her. She says that the woman helped her a lot.

Fighting against the system

She helped her file a petition at the court demanding the government to consider transgender as equal citizens and give them the right to get permanent jobs as teachers in colleges and universities. Faizi won the case, but she couldn't pass the lecturer's examination of the Punjab Public Service Commission (PPSC). However, she has been teaching since 2011. She did her B.Ed. from Lahore. After that, she got an internship at a government school. She taught there for one year, and then she taught in some government and private colleges for several years. She also taught in some private tuition centres. She is Pakistan's first trans teacher.

Faizi is now working as a victim spot officer in a protection center developed by Punjab police in the district of Toba Tek Singh. She wants to go back to teaching. She is planning to get admission in a PhD program in Urdu at university, and after completion of her PhD, she will apply for jobs in the university

I was molested as a child

Ali Rehman,* a businessman from Lahore, was molested as a child at a local Islamic seminary. He does not talk about it anymore due to the social stigma attached to it, but the trauma is there.

"It was difficult for me to talk about this," he said. "People often think men cannot be victims of violence. But it does happen to us."

According to the recent report of a nongovernmental organization Saahil, an average of 12 children per day faced sexual abuse in Pakistan in 2023. The report further revealed that younger boys had suffered abuse more than younger girls. Saahil collects these incidents from newspapers. Hence, the real situation could be even worse. Many incidents of violence against younger boys occur in seminaries. Ali recalls his own experience as a seminary student when a teacher attempted to coerce him sexually.

"One day, a teacher called me to his house for what I thought was work. But when I arrived, he was sitting there naked. I immediately ran away," Ali said. "I was scared to tell anyone since I’d never heard of a boy reporting such things, especially to parents."

Toxic masculinity attitudes in Pakistan often prevent male victims from reporting sexual violence. Seeking justice is seen as a shameful weakness rather than a tremendous strength. Victimhood also triggers feelings of humiliation due to cultural notions linking "honour" to macho dominance. Most, thus, stay silent, leaving psychological trauma unaddressed as systems ignore male vulnerability.

Ali, however, told the incident to some of his classmates, who he says to date make fun of him. They mock the traumatic experience, laughing at his "missed opportunity" whenever the seminary name surfaces in their conversations.

“Fifteen years have passed since this incident. The friends whom I told about the incident at that time still make fun of me asking what would have happened if I had stayed there. Then they laugh. I don't even repeat this incident now, but whenever the name of this teacher comes up, or the name of the seminary comes up, my friends start making fun of me, saying that he was crazy about you,” he added.

"Sadly, rigid gender norms and toxic views of masculinity fuel violence against marginalized groups in our society," explains Shermeen Bano, a sociology professor at FC College Lahore. "It's not just restricted to women—men and transgender individuals are also disempowered and dehumanized due to their gender identity."

Shermeen traces the roots of this systemic issue in Pakistan to deep patriarchal attitudes and structures of inequality engraved into the fabric of society. She says the gender against violence in our society happens at different levels.

"It happens at the individual level, within family and community networks, as well as societal and state levels. Those seen as lacking power or dignity due to their gender identity become targets. For transgender individuals, violence and restricted rights stem from their failure to conform to the gender binary. Male victims also lack power—strength is equated to masculinity, so sexual abuse of men and boys goes unacknowledged," she said.

Dr Rubeena Zakar, a Public Health professor at the University of Punjab, while talking about Gender-based violence in Pakistan especially one targeted at those who are not women, said that many of those cases go unreported. Even the cases of violence against women go unreported.

“When you see incidents of gender-based violence in the media, they are against women. But the violence against men, we will not say that it does not happen, but it does happen. Incidents of violence by women against men are very few, but incidents of violence against women by men are very high," she said.

The discrepancy stems in part from societal attitudes that frame feminine victims as more sympathetic while masculine vulnerability remains taboo.

"Ours is still very much a patriarchal society stacked in favour of men and rigid gender norms. So, violence against women gets highlighted more," she said.

However, data suggests alarming rates of abuse against marginalized male and transgender groups.

"Make no mistake - male-on-male sexual violence is very common in Pakistan, but notions of masculinity and honour prevent victims from coming forward," she stressed.

The result is a perfect storm where oppressed groups suffer violence quietly due to stigma, inadequate legal protections, and lack of social support.

She says that this violence stems from the society and its parameters for different genders. If it considers a gender lesser being, that gender will suffer more violence and have even lesser support.

"If we as a society view someone as 'other' or inferior due to their gender identity, that enables serious abuse. Transgender individuals, in particular, face huge discrimination and vulnerability to harassment,” Dr. Rubeena said.

How the Situation Could Be Changed?

Both Dr. Rubeena and Shermeen said that we would need to change the way we look at vulnerable groups as individuals and as the whole society. Then there is a need for wide-scale awareness campaigns and systematic changes that give power to these groups and make them equal citizens of this country.

"We need to empower vulnerable groups and give them greater autonomy and dignity regardless of gender identity. Simultaneously, we must challenge traditions and norms that justify misogyny and bigotry. Only then can we envision a society free from violence for people of all genders,” Bano said.

Dr Rubeena says universities should play their role in this regard. Those should take the help of their students and send them to communities to work as change agents.

"Legal initiatives, counselling services, university gender programs - these can help. We must go deeper within communities to shift mindsets and toxic masculinity norms that fuel violence against marginalized groups,” she said.

It is a long road, but an essential one to build a society free of oppression.

"The most vital need is awareness - we must break taboos and start openly discussing violence targeting men, transgender citizens, and anyone else who suffers abuse. Only then can all people live with equal rights and dignity, regardless of gender," Dr. Rubeena said further.

The path forward winds through schools where curriculum and counselling nurture inclusion; through homes where families reconcile rigid roles, and seats of power occupied by visionaries bold enough to legislate protections for all. The healing should begin in communities reclaiming identities that have been long demonized. Media should also play its due role in this regard by giving an amplified voice to the muffled trauma of marginalized groups.

As Shermeen stated, such transformation requires “redefining strength” as empowering the most vulnerable—countering decades of trauma with resilience. The space must open through dialogue; laws should be made to secure rights for everyone regardless of any discrimination Though long suppressed, an enlightened Pakistan lies within reach should we muster collective courage to confront bias in all its insidious forms.