December 7, 2023 - Comments Off on The Tight Slap – Pakistani dramas and the blurred lines between imitating and Influencing life

The Tight Slap – Pakistani dramas and the blurred lines between imitating and Influencing life

Sabah Bano Malik

Trigger Warning: This article covers topics including femicide, domestic violence, domestic abuse, and marital rape.

In 2014 I resigned myself to watching with my mom whichever drama she was currently consuming. This was before I understood how streaming worked, or torrents, or how to cast something to a television once you downloaded it (needless to say, I was technologically challenged), so she ruled the remote and therefore the content.

In 2014 I resigned myself to watching with my mom whichever drama she was currently consuming. This was before I understood how streaming worked, or torrents, or how to cast something to a television once you downloaded it (needless to say, I was technologically challenged), so she ruled the remote and therefore the content.

One drama in particular had ensnared her and truthfully me as well. To be honest, as much as I do criticize dramas, they really do know how to get you sucked in. Dramas are watched by millions – leave the television numbers aside, the views on YouTube where channels now post whole episodes soon after they air on television, regularly cross millions in views. Stories about families and shaadis dominate the plot points, but now and then you get a drama which puts a bit of a twist on the tales as old as time, so it was not uncommon for me to grumble but also ask my mom to catch me up on anything I had missed by the time I started watching.

This time around, she was watching Bashar Momin, a serial that centered around the titular antagonist turned protagonist Bashar Momin. The central plot was around him and his relationship with his wife Rudaba, played by Faysal Qureshi and Ushna Shah respectively.

What made this drama a bit different was it seemed to slightly borrow from the common tropes of Turkish dramas known to meld mob and love plots together, Bashar was a gangster, money launderer, all around bad-guy in impeccably-tailored shiny suits who took up space in a menacing way. He was clever with evilly crafted one-liners. He was also handsome, rocking a well-coifed mop and a shaped-up beard that at the time was the most sought-after look and continues to be the dominant fashion trend with young men. He was an anti-hero that grew so popular that even in contentious times streaming rights landed in India for the show to air there as well. Rudaba was in many ways a fighter, but in overwhelming ways she was what most of our heroines in our dramas are: trapped, stuck, unheard.

Even in this drama about a bad, bad guy, shaadi could not be far behind. It is the most critical of plot points when it comes to our entertainment. Nothing can start and nothing can end without shaadi somewhere in there.

Circumstances lead to Rudaba marrying Bashar, neither is particularly happy about it. Though Bashar did manipulate the nuptials into happening – Bashar the older, the conniving, the have I mentioned bad guy, manipulated her brother into marrying her off (no consent necessary, just threats and duty cited) to him. Rudaba was afraid of him.

I am talking trembling, eyes averting, this is a bully and she is the cornered type afraid of him. He was mentally torturous of her and often verbally abusive, and would be seen routinely grabbing an arm or physically intimidating her by blocking her path or towering over her. And if one was to assume he took being a husband seriously – he was also emotionally neglectful.

Not to mention he broke up her long-time engagement to a family friend (promised by her dad, because of course) and was overall making it so that everyone in Rudaba’s life doubted her character – which they did very easily, because well, art imitates life and who has it easiest to destroy a woman’s character than literally any man determined to do so and the fact that there is always a willing to listen audience for them.

So when a few episodes went by and Bashar told her to get out and he was going to divorce her, I was quite literally scooping my jaw up off the floor to hear that he could not do that to her because she was pregnant.

She was pregnant.

As of today, there are no official laws on the books in Pakistan that explicitly state or acknowledge the reality of marital rape, the act of sexual coercion and assault between married persons. However as stated in this article in January 2023 written by Forman Christian College, “The legal provision against rape in the Pakistan Penal Code[1] doesn’t explicitly mention marital rape but still the provision recognizes sexual intercourse insides the bounds of the marriage as rape if it takes place against the will of the wife.”

Unhappy wives falling pregnant on our television shows is very much the norm. It is also not uncommon to be introduced to a long-suffering wife who has many kids with her abusive, shitbag of a husband. It is also not uncommon to see having children being prescribed as the quick fix for a horrible marriage being depicted on screen.

But rarely if ever is it acknowledged that two people who despise each other seemingly made children, and in the cause of Rudaba and Bashar it stuck out to me so much, that I am reflecting on it nearly ten years later, because only an episode earlier I watched her shake in fear at sharing space with him – and putting two and two together, broke me.

“So was it rape?”

That’s the question I posed to my mom whose eyes widened like she had not really thought about it like that before, because to marry and to have children just kind of happens. It’s the expected next step no matter if you’re arranged, in a love match, or in so many cases as seen in our dramas, and sadly our headlines, forced.

When marital rape is brought up online where I chronically live, I can pretty much guess exactly what is going to happen in the comments – men claiming it is not real. Men demanding to know what the point of them earning money is then, implicitly stating that they are buying their wife’s consent. Men saying feminism is ruining families, because consent is a made-up concept.

I kid you not, a man once responded to one of my Tweets (my X’s?) about marital rape saying, “Consent will ruin marriages,” another simply wrote, “Consent?” punctuated with about 20 laughing emojis.

The idea that a wife is giving consent for life by marrying you seems to be the believed doctrine of too many people, so when I criticize dramas for continuing this point in their plots am I critiquing them for portraying culture or for influencing it?

Should Pakistani dramas talk about whether consent has taken place? Could they be doing more? Should they be doing more?

According to a study conducted by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) titled 'Factsheet on Domestic Violence During COVID-19 Lockdown'[2] in 2020, 90% of Pakistani women have experienced some form of domestic violence in their lifetimes.

90% of us, and that’s just who felt confident enough to say so. Or who felt it was so normal it was not something they needed to hide or deny. Imagine the numbers if we could ask everyone. If we could inform everyone.

There’s a casualness around the unequal dynamic in the relationship between husbands and their wives in our culture. An accepted truth that the husband is the boss and what he says goes – you see it a lot in our dramas too. Freshly wed brides are suddenly being dictated to about what they can wear and who they can see. Wives divert attention and life-changing decisions to their husbands or other males in the family. And that’s sadly not even shocking enough to be the whole point of the show – fighting those very ideas – but just how things are done. Because that is how things are often done.

Before I dive into physical domestic violence and its depiction on our televisions, I want to talk about the other types of abuse that are so common place in our dramas it genuinely gives me chills because if it’s so normal on here, that means it’s so normal out there in the real world.

Let me set the scene. A man comes home from the office, he’s already in a bad mood because his mom or his cousin who actually wants to marry him has been calling him all day complaining about his wife. His wife who has run the household all day and is now waiting for him to get home hoping beyond hope he is in a good mood because since they married, he rarely is, is waiting in their room.

He enters, she says hello, maybe takes his jacket and his bag, brings him a glass of water she already had prepared, and he says nothing. No hello. No acknowledgement.

She tries to pepper him a bit, get him conversing, and make some polite conversation – if she is unlucky, she will be addressing some conflict that was left to her to resolve. And then he snaps!

“Chup! Bas!” The beloved quips of, “Do you ever stop talking!?” and “My mother was right about you!” or “Go crying to your brother, see if I care.”

In some dramas here is where the accusations will be meted out against her character, or demands will be made of her to be better than she is, and if the writers want to spare us, he will slam the door on her and walk out.

Ridiculing wives, degrading wives, ganging up on wives – all of these seem to be seamlessly apart of the majority of Pakistani dramas.

Now often this behavior is not dismissed by the audience, or at least it is not meant to be – that would not be fair of me to say, clearly, we are meant to look at this chump and know he’s in the wrong – but it’s how this wrong is often dealt with that jolts you out of seat and makes you want to shake your tv screen.

Women are expected to suffer and sabr, and suffer and sabr, and ultimately get their win at the end of the day by forgiving everyone who wronged her and being just the purist, sweetest, likely light-skinned angel that one could be.

She forgives abuse, she forgives isolation, because well she’s above making people pay when she can play nice. She sees her husband has come around and she can forgive him, or she can let him be their children’s lives, she can even hug her abusive collaborators, or she can forgive her own family for marrying her off.

Which influences the audience to believe that women should suffer. Women should sabr. And women should forgive. At least good women do.

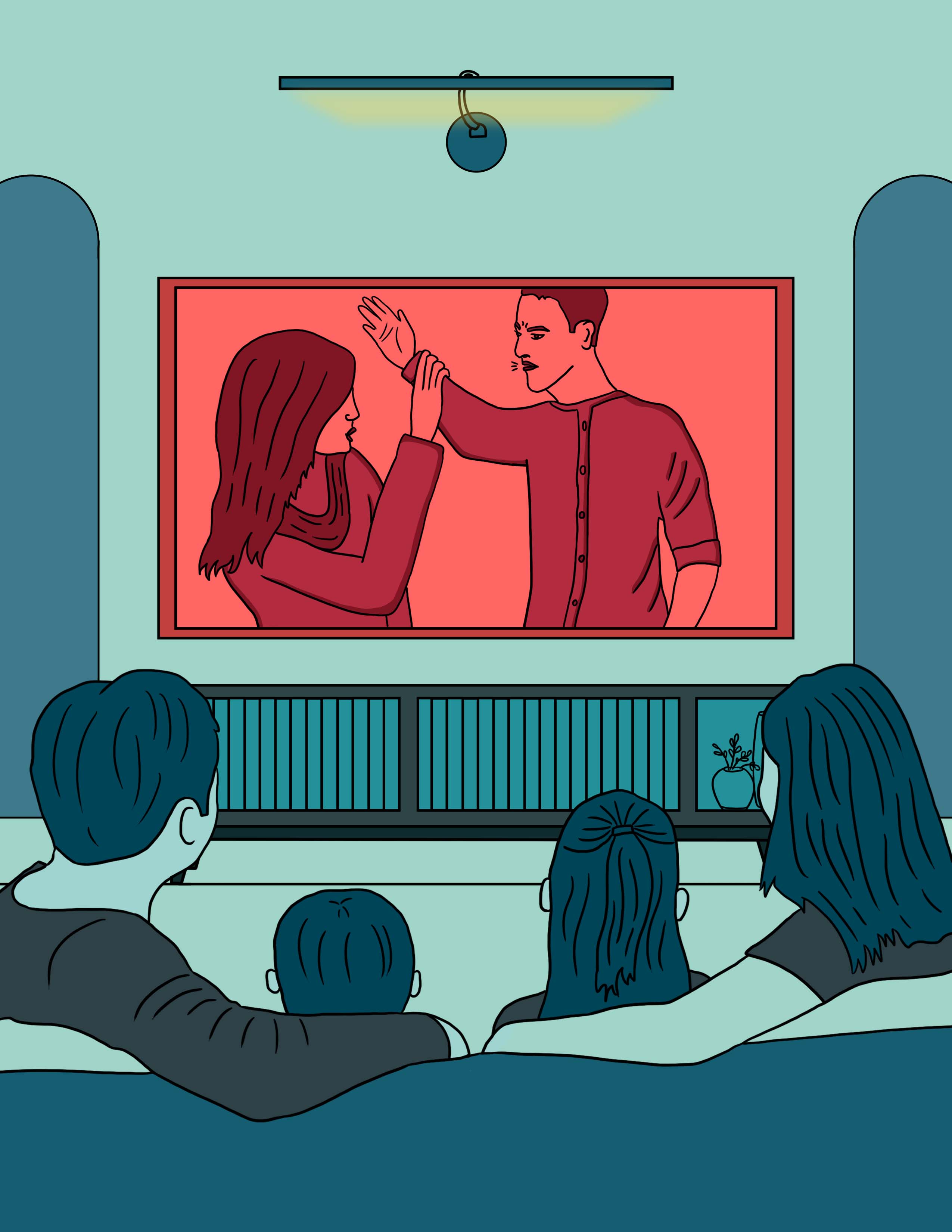

This is even the case when domestic physical violence takes root.

The problem is, with 90% of Pakistani women reporting being at the receiving end of violence at some point in their life, is it simply art imitating life, and if so, how much responsibility does art bear to challenge the norms of life?

It's not just slaps, but arm grabbing, arm shaking, physical intimidation, shouting, and the aforementioned very much present "marital rape" in dramas - all being normalized. And when the knee-jerk reaction of the country, including those in entertainment, is to brush off violence, how long can we let this "norm" be the norm?

Nowadays when a slap is heard on television dramas it can often lead to outrage on the internet – but that’s for the popular shows, the ones that have fanbases online and often tap into younger audiences. But slaps are as regular of tropes about girls in jeans and those who work in offices – the latter two quite negative, the slap – just part of what we do.

A husband lifting his hand against his wife is not only uncommon but expected, often in these shows (and I dare I say real life) a wife will sometimes be consoled and comforted but also told that this is sometimes just what husbands do.

So again we can say art is imitating life, then what responsibility does art hold? In a country with rampant (at times denied) femicide and women’s patience and hurt and endurance seen as an integral part of our culture – should the shows do more to battle these expected realities?

For some people seeing harrowing or even casual instances of domestic violence may strike a chord, and may even change their opinion on things – but when there is an overwhelming dismissal of violence against women – especially within the confines of a marital home or family unit – should dramas be doing more?

I personally think – yes. And I am not alone.

Just last year the drama Tere Bin starring beloved drama actors Yumna Zaidi and Wahaj Ali was THE drama everyone was talking about. It was a massive success not only here in Pakistan, but in Bangladesh and India as well and it did what not many dramas are doing – it captured Gen Z and it became part of internet culture. Forums, threads, groups – they build a devoted fan base and largely due to their slightly unconventional, leaning slightly more contemporary handling of the central relationship of the series of Meerub and Murtasim. They literally talked about consent believe it or not.

Meerub was a departure from the usual heroine – brash, wild, bold, and at times wholly unlikeable, and Murtasim was the grumbly rough hero softened by his love for this wild girl – the makings of drama deliciousness. But then he slapped her.

He slapped her and it was romanticized by the show. And by the audience.

In order to write about this moment, I went to watch it on YouTube, the clip has 2.3 million views and thousands of comments and many of those disgusted with the romantic portrayal of the slap in turn had hundreds of comments saying, and I quote, “Aisa hi romance real hota hai.” Many also said she pushed him to it, this was his first time reacting, he felt bad, and he said sorry, it happens. It happens.

It happens.

Maybe the most dangerous and the most telling of the commentary on the slap and the swoon-worthy way it was portrayed was two words: it happens. Because it happens is a stone’s throw away from “this is just what husband’s (or men) do.”

Fans were outraged and talk around the slap was trending on social media with literal hashtags about the slap itself racking in thousands of posts and critiques and demands for the drama industry to do better, to stop using abuse as a plot point if they were not going to handle it with care, respect, and satisfying retribution.

And this could possibly be why the show took a harsh pivot on a marital rape scene that would come and stun everyone being that a huge plot point was around their marriage being approved by Meerub when she got in writing that no consummation would take place without her consent.

The marital rape scene in the drama was rebranded as a “regret” moment when it became clear the audience was not going to be on board with the torture of the heroine, it was handled incredibly clumsily and audiences did not let the show off the hook. Ridiculing and condemning the show with equal energy. Watching the scene back now it’s hard to see where they believed shoddy editing could save this – we all saw through it; it was violent and transparent.

And it was wholly unnecessary. But it gets views. Marital rape, mentions of rape, slaps, abuse, traumatized and crying women – it all obviously leads to views because these dramas become huge, viral, record-breaking shows. And again I ask, what responsibility does the drama industry have to highlight abuses happening in our societies but also treat them in such a way that their massive influence can be used for good?

There is also a ridiculous amount of arm grabbing in our dramas. Arm grabbing has long been seen as the out-of-control urge to hold someone that entertainment coming out of more conservative cultures have employed for eons.

Arm grabbing is big in K-dramas, Turkish dramas, and of course, Bollywood where there was nary a film without an arm grab or even an arm drag, and they are also frequently happening in our own Pakistani dramas.

It’s almost always portrayed as emotional turmoil pushing a man to this, it is romantic. It is manly. And it is so dangerous. I am 34, I have been watching Bollywood movies for three decades, Pakistani dramas for closing in on two and even I find myself having to dismantle daily what is romance, what is care, what is healthy in relationships because what we accept as norms and portray as norms cannot be.

Published by: Digital Rights Foundation in Digital 50.50, Feminist e-magazine

Comments are closed.