January 31, 2017 - Comments Off on Harassment as a Legal Concept in Cyber Law

Harassment as a Legal Concept in Cyber Law

Harassment as a legal concept finds its origins in, and is deeply embedded in, the context of the workplace. This is not to say that harassment only takes place in those spaces, but simply because the concept was first articulated legally in the context of workplace discrimination and is thus finds its first formal articulation in the Protection against Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2010. This conception of harassment takes it as a form of sex discrimination. There are other articulations of harassment as well, such as a breach of privacy or an affront of dignity.

Harassment, unfortunately, is a fact of life for many women in spaces other than the place of work. Most public spaces are hostile environments for women. It is for this reason that street harassment is also criminalised under section 509 the PPC in Pakistan. It comes as no surprise that cyber spaces are no different when it comes to the experience of women and minorities. Out of the 3027 cybercrime cases reported to the FIA during August 2014- August 2015, 45% involved electronic violence against women (e-VAW).

Given the relative newness of online spaces and platforms, and their ever-evolving nature, cyber harassment as a concept has not been as well defined as its other counterparts in other spaces. Prior to the passing of the cybercrime bill, much of the anti-harassment work was being done by section 36 of the Electronic Transactions Ordinance, 2002 (ETO) relating to privacy of information. Privacy is an interesting jurisprudential lens to view anti-harassment legislation through. This currently is the approach taken in US jurisprudence through the developing field of the right to sexual privacy. However in order for cyber harassment to be effectively tackled through this legal paradigm, there needs to be developed jurisprudence around the right to privacy.

Under the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2015 (PECA, or the Cybercrime Act), section 21 (offences against modesty of a natural person or minor) and section 24 (cyber stalking) deal with the issue of online harassment. These laws, while a step in the right direction towards talking online violence seriously, are both overboard in their reach and inadequate in effectively tackling harassment in online spaces when taken at face value.

The laws have been widely criticised for the vague, and often careless, language that they contain. The definitions relating of modesty of natural persons are meant to capture non-consensual pornographic content. However over-reliance on concepts such as modesty and the explicit absence of the legal requirement of consent leaves something to be desired. Furthermore, cyberbullying legislation have faced many constitutional challenges in many other jurisdictions around the world—challenges being mounted mainly from a free speech and censorship point of view.[1] It is up to the interpreters of these laws, by cybercrime lawyers and designated judges, to develop jurisprudence that benefits the victims of these crimes without impacting free speech. The broad language of the sections can be reined in by thoughtful interpretation and reasoned discussion on the contours of free speech in a democratic society.

The definition of “cyber stalking” under section 24 of PECA covers a wide range of activity. Since this is a criminal statute, interpretations of the section need to guard against actions which do not rise to the level of criminal reprimand—a threshold that the text of the Act does not lay out itself. Furthermore, judges need to interpret the section with the true spirit of consent jurisprudence. This is particularly important when it comes to section 24(d) where even if the initial photograph or video was made with consent, it is the non-consensual distribution that needs to be criminalised. While non-consensual capturing of images should also be penalised in and of itself, the illegality of non-consensual distribution should operate independent of and decoupled from the capturing of the images.

When it comes to online harassment, there is a particular element of urgency given the reputational damage at stake and the possibility of duplication of information. This is where the procedural aspects of the law play a significant role in taking down content in a timely manner. Getting images removed from the internet is the immediate need of many complainants, and the PECA does not speak to this urgency. The aggrieved person can apply to the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) to remove images implicated by sections 21 and 24, however there is no mechanism in place to ensure that this happens before the reputational damage is done.

In the United States, removal of images is done through the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 through a notice of copyright infringement. This is an interesting method to tackle online harassment, one not without its demerits. However again, given the dearth of case law and legal work around concepts of property in digital spaces it is unclear if such a mechanism is even feasible in Pakistan.

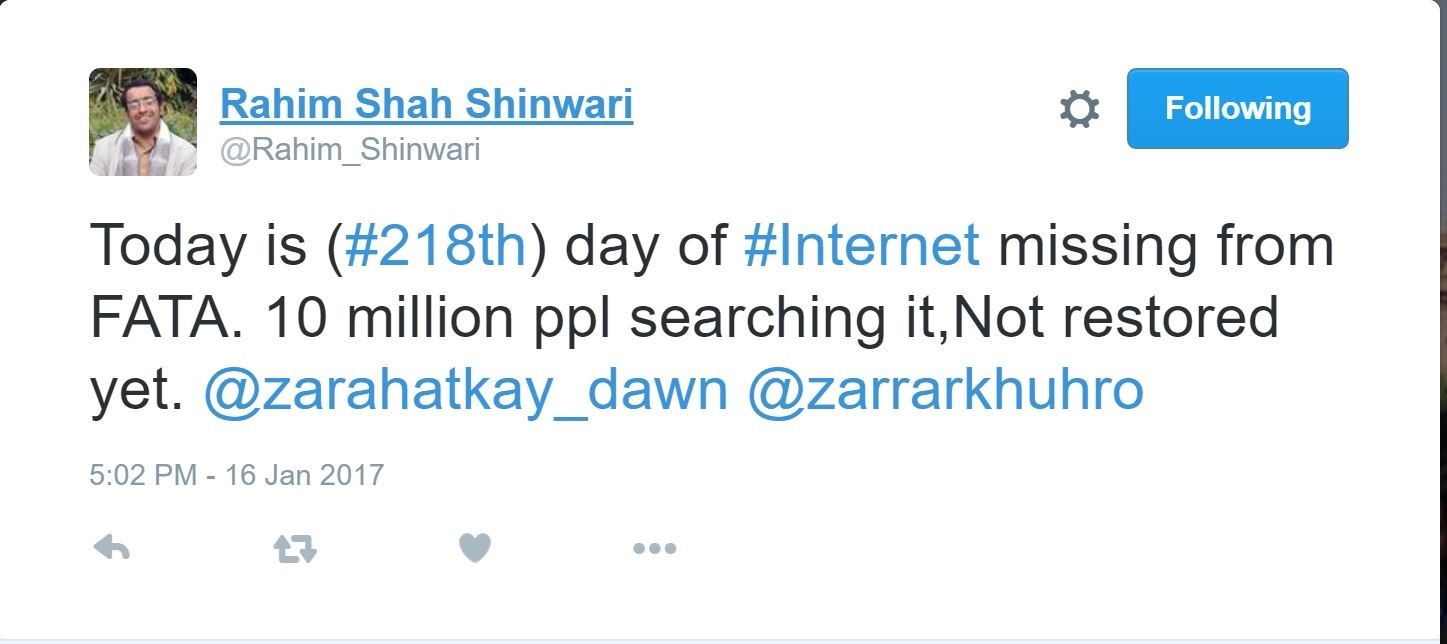

Returning to the concept of harassment in general, it would be useful to see the phenomenon of online harassment from the perspective of the right to equality. Just like harassment at the workplace is a form sex discrimination, it can be argued that given that harassment in cyber spaces mostly effects women and marginalised communities, it is a violation of their right to equal access to and enjoyment of the internet.[2] This conceptualisation is not found within the PECA, which is primarily a criminal statute, but a rights-based approach to digital rights needs to view online harassment as an issue of civil rights.

Lastly, another aspect of the law that is particularly egregious for victims of online harassment is the lack of anonymity in reporting instances of such activity. The humiliation of reliving the experience that the victim has been through and the indignity of turning in evidence, sometimes involving sexually explicit material, to predominantly male police officers and judges can be a traumatic process. Law enforcement agencies and the subsequent court system needs to be cognizant of these social and psychological aspects when investigating and adjudicating such cases—a consideration that should inform their legal analysis and judgment.

This legal note originally appeared in "Three Pillars" law magazine (January, 2017).

[1] Section 66A of the Indian the Information Technology Act, 2000 was struck down on grounds of violating free speech in the 2015 case of Shreya Singhal v. Union of India.

[2] Danielle Citron, “Hate Crimes in Cyberspace”. Harvard University Press (2014).