October 4, 2023 - Comments Off on Unveiling the Human Side of Data: The Journey of a BISP Beneficiary Denied Ehsaas Programme Access

Unveiling the Human Side of Data: The Journey of a BISP Beneficiary Denied Ehsaas Programme Access

By Sara Atiq

Whenever our policymakers, politicians, or CEOs of corporate companies mention terms like “policies informed by data,” “data-driven analytics,” or “processes facilitated by AI,” we instantly equate it with transparency, fairness, and infallibility. Many mistakenly believe that “data” equals “fact,” and anything based on facts is considered the ultimate truth. However, it's crucial to recognise that 'data' can carry biases, and algorithms built on such data can inadvertently exacerbate existing disparities, mainly when employed in the identification, categorisation, and decision-making processes that profoundly impact marginalised communities' welfare and well-being.

Whenever our policymakers, politicians, or CEOs of corporate companies mention terms like “policies informed by data,” “data-driven analytics,” or “processes facilitated by AI,” we instantly equate it with transparency, fairness, and infallibility. Many mistakenly believe that “data” equals “fact,” and anything based on facts is considered the ultimate truth. However, it's crucial to recognise that 'data' can carry biases, and algorithms built on such data can inadvertently exacerbate existing disparities, mainly when employed in the identification, categorisation, and decision-making processes that profoundly impact marginalised communities' welfare and well-being.

Data-Defined Exclusions: Unmasking 850,126 'Undeserving' Cases in BISP

At first glance, the idea of 'biased algorithms influencing critical policy decisions' may seem like a concern limited to technologically advanced nations, with countries like Pakistan appearing far removed from such issues. However, this is not the case. This is the story of Pakistan and how, when data is utilised to make significant decisions without considering the socio-economic and political context, it can further marginalise those already struggling.

In 2019, during the tenure of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf government, the then-chairperson of Pakistan’s most extensive social safety net program, the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP), which was later rebranded as the Ehsaas program, announced the removal of 850,126 individuals deemed ‘undeserving’ for BISP benefits. Dr. Sania Nishtar, in an op-ed published in an English daily, explained the rationale behind this decision. When Dr. Sania took charge of BISP in 2018, the government was providing stipends based on a decade-old and paper-based survey. According to her, this survey contained numerous errors in both inclusion and exclusion. Dr Nishtar claimed that, besides deserving beneficiaries and pensioners, “relatively well-off individuals and many government servants were benefiting from the program.”

Then, there were those whose financial situations had shifted since they first signed up for the program in 2011. How did BISP pinpoint these individuals? This is where the 'data-driven decision' comes into play. Dr Sania said this intricate task was entrusted to a computerised system guided by a rule-based wealth-profiling data analytics process. She said, "A rule-based wealth-profiling data analytics process was employed, leaving no room for 'human intervention', to correct the BISP's beneficiary lists before their integration into the Ehsaas program."

The argument favouring minimising human intervention in processes like these to ensure objectivity and transparency is compelling. However, it's vital to understand that, much like humans, data can carry biases. This is because individuals collect data and reflect the perspectives and inclinations of those who gathered it.

When an algorithm, essentially a set of precise instructions tailored for a specific task or problem-solving, is trained on such biased data or lacks the necessary cultural and political context, it can inadvertently perpetuate ‘unjust’ outcomes. The case of BISP serves as a vivid example of this seemingly complex phenomenon.

Following the PTI's exit from office and the PDM assuming control, they criticized the removal of 850,000 beneficiaries, branding it as 'unfair' and 'politically motivated.' Subsequently, an appeals process was announced for those who were declared ineligible. It's important to note that the intention here is not to assert that the entire exercise or process was 'unjust' or 'erroneous,' nor to speculate on whether the decision was politically motivated. Instead, the focus is on underscoring the ethical considerations that may have been overlooked in the implementation of this 'data-driven' approach.

While this process may have been effective in accurately identifying several beneficiaries who were either mistakenly included or whose financial circumstances changed over time, rendering them ineligible for the program, there were beneficiaries who were removed from the list due to a lack of social context in the data analytics process. The process may seem scientific and efficient, but it failed to account for the inherent biases present in the data itself, leading to potentially undeserving exclusions. Data systems built on biased data perpetuate and amplify these biases, making the need for human context and intervention all the more crucial.This highlights the need for a more nuanced approach when applying data-driven methods in sensitive decision-making processes.

Context-less data creating mischaracterisation and marginalisation

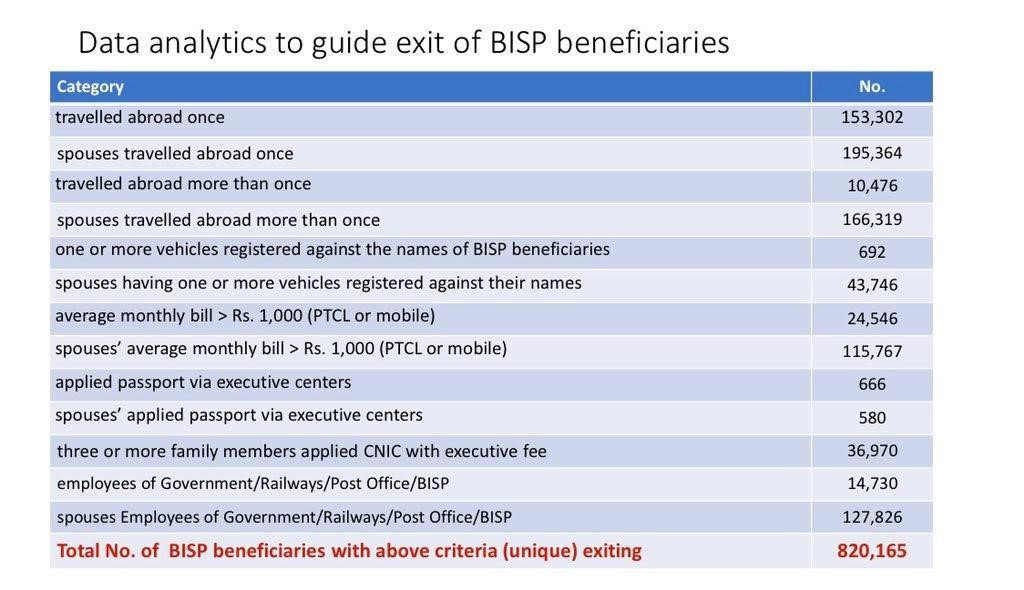

Let's delve into how the criteria for exclusion were formulated, leading to the disqualification of over 8.5 lakh beneficiaries from the Benazir Income Support Program, a crucial social protection initiative. This program provides eligible families 12000 Rs quarterly unconditional cash transfers (UCT). To assess the current economic standing of the beneficiaries and classify them as 'deserving' or 'undeserving' of the program, specific parameters were established.

To gather beneficiary data, information was obtained from the Pakistan National Database NADRA, as well as other relevant government agencies. According to official reports, various wealth indicators, developed in consultation with NADRA, were employed as exclusionary filters. These included criteria like international travel, ownership of a car (with motorcycle owners exempted), an average six-month telephone bill exceeding Rs1000 per month (covering both landline and mobile usage), processing of passports and national identity card numbers by three or more family members through Executive Centres, and government employment. According to Dr Sania Nishtar, these wealth indicators were approved by the cabinet.

On the surface, these criteria may seem reasonable for assessing one's economic status. However, without additional context, this information alone was insufficient for accurately determining wealth status and overall social well-being. This is where human judgment and intervention become crucial, as relying solely on algorithms could lead to outcomes solely based on available data, potentially missing essential nuances.

"One of the exclusionary criteria centred on international travel. It was only during the appeal process that we came to realise there were beneficiaries who were excluded because they had travelled abroad at least once in their lives. What we failed to consider was that in our country, even the most marginalised and needy individuals would often save every penny throughout their lives to embark on religious pilgrimages like Hajj or Hindu yatras. Alternatively, they might receive assistance from philanthropists. However, this doesn't necessarily translate to an improvement in their daily lifestyles or economic conditions," shared Shazia Marri, the former BISP chairperson who succeeded Dr. Sania Nishtar. After taking charge, she announced an appeal process for those who felt they had been unjustly removed from the beneficiary list.

“Likewise, one of the wealth indicators was ownership of a car. We had a beneficiary approach us, explaining how he inherited an old car from his grandfather, which was transferred to his name. home, the car remained parked on the street. In another case, we encountered women who didn't possess a national ID card. When this programme was first introduced, they took out a loan to expedite the processing of their own and their family members' IDs at executive offices.”

According to BISP officials, “in order to redress the grievance of blocked beneficiaries, BISP Management decided to design an appeal mechanism. However, due to challenges in the availability of relevant data and the non-integration of various databases, the appeal mechanism could not be fully implemented. However, on the basis of decisions of the BISP Board, the profiling filters (with the exception of two filters, i.e. government employee and high income) were removed, and beneficiaries were included irrespective of the fact that they filed for an appeal, provided they fulfil other mandatory criteria for inclusion.”

Ms Marri emphasised that even individuals who had previously travelled abroad owned a car, or processed their CNIC at an executive centre found themselves among the blocked beneficiaries, receiving a PMT score of 32 or lower upon re-evaluation by the BISP team. The PMT Score in BISP encompasses specific factors and parameters that determine eligibility for various programs, including the Ehsaas program and BISP subsidiary initiatives. These factors encompass family total income, expenses, total family members, and income sources, all of which are taken into account to compute the PMT Score in BISP. Families with a PMT score of 32 or lower meet the eligibility criteria for BISP registration.

According to numbers shared by BISP, out of 820,165 blocked beneficiaries, 262,291 beneficiaries have been re-included in the programme. Of this, 139,029 have started receiving payments, while 123,262 will be enrolled for payments during the next enrollment cycle. There are multiple reasons for beneficiaries who are not included in the programme. This blocking was based on the previous NSER, and after the NSER update, many of the blocked beneficiaries have either not opted for the survey or have PMT more than the new eligibility cut-off of 32.

No transparent data processing.

The global discourse on data ethics and privacy has put a spotlight on the responsible use of data and data processing. Even in Pakistan, though imperfect, steps are being taken towards data protection with the proposed Data Protection Bill and AI policy. As per the draft bill and policy shared by the Ministry of Science and Technology, ensuring transparency in data processes is a priority. It is now mandatory for data controllers and processors to seek consent from individuals when their data is collected and processed for a specific task.

This leads us to an important question: Were the beneficiaries of BISP informed when their data regarding travel history, vehicle ownership, and national identity card processing was collected and processed to assess their current wealth status?

Ms. Marri, upon assuming her role, promptly raised this question with the team overseeing the development and implementation of these wealth indicators. She sought to understand whether the beneficiaries were given an opportunity to provide context or clarification regarding this new information. It became evident that these beneficiaries were never informed of the data collection process. Ms Marri believes this was not only a matter of transparency but also an ethical concern.

In the evolving landscape of data-driven decision-making, the case of BISP serves as a poignant reminder of the critical balance required between technological advancement and human compassion. As nations and institutions increasingly turn to algorithms and data analytics for policy formulation, it becomes imperative to acknowledge the inherent biases that can be entrenched in the data we rely on.

The story of the 850,126 beneficiaries excluded from the Ehsaas program is a stark illustration of the potential pitfalls of such reliance on data alone. While the intent behind using algorithms is to streamline processes and remove subjective judgments, this narrative underscores that context, nuance, and a deep understanding of the socio-economic realities of individuals cannot be replaced by lines of code.

The ethical dimension cannot be overstated. It prompts a critical examination of the responsibility that comes with wielding the power of data. Transparency and informed consent must be the bedrock of any data-driven initiative, as highlighted by the proposed Data Protection Bill and AI policy in Pakistan.

Ultimately, the story of BISP and the ensuing appeals process serves as a call to action, urging policymakers, technologists, and society at large to approach data-driven decisions with vigilance and empathy. It is a testament to the enduring importance of human judgment in an increasingly digital world and a reminder that progress should never come at the expense of those most in need.

Published by: Digital Rights Foundation in Digital 50.50, Feminist e-magazine

Comments are closed.