September 7, 2017 - Comments Off on Is the collection of student data by LEAs permitted by law?

Is the collection of student data by LEAs permitted by law?

In the wake of an attack on the leader of the Opposition in the Sindh Assembly, allegedly carried out by a Karachi University student, concerns of student militancy over the years continue to grow. In this context, the aim of the collection of private student data by law enforcement agencies (LEAs) is to ostensibly track and curb potential involvement in terrorism.

The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA), passed in 2016, does provide a mechanism whereby an authorized officer may by notice, require universities to provide or preserve the specified data for up to 90 days and only bring to the notice of the court within twenty four hours after the acquisition of the data. The court may issue a warrant for disclosure, furthermore, if the court is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for the purpose of preventing crime.

It is unclear, therefore, as to which provisions law enforcement agencies (LEAs) will be relying on in order to legitimise such large-scale data collection. Simultaneously, there are no direct data protection laws in Pakistan that would challenge this invasion of privacy. Further to this, the security agencies that the LEAs will be working alongside have yet to finalise or even develop an effective mechanism in regards to data collection and with respect to privacy.

The PECA provisions listed above, furthermore, are only strictly applicable in relation to ‘ongoing’ criminal proceedings or investigation and cannot be used as a tool to profile or surveil all university students under the guise of national security. As a nation with security state characteristics, Pakistan has troubling precedent in regards to overriding fundamental human rights in the name of security, and which we could see happening here.

There are similarities that could also be drawn between student data collection and the compulsory SIM registration policy by NADRA, which were promoted and created as a means of cracking down on potential terrorists. It is likely that a similar policy would be adopted by the security agencies, using much the same justification.

Putting private data of university students under intense scrutiny could exacerbate an already stressful atmosphere - students are required to provide “character” certificates when being admitted, and there is an increase in CCTV monitoring at entrances and exits of several campuses across Pakistan. Such mass surveillance of students must be condemned, as this would harbour distrust and anxiety in students. Rather than make them feel safer, mass surveillance would actually increase feelings of insecurity, as they would feel unable to express their views freely.

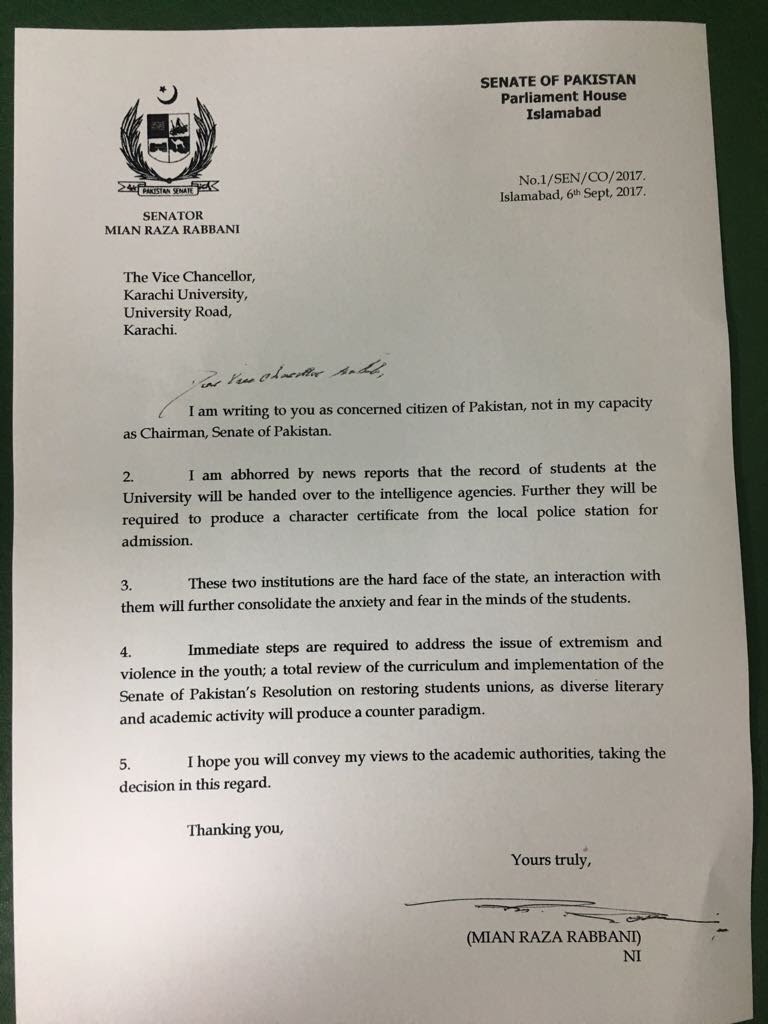

Data collection and other aforementioned anti-terrorism actions by the state have thus far generally failed to garner support, even within parts of the government. Senator Raza Rabbani echoed concerns similar to ours in a letter (which can be found at the end of this post) addressed to the Vice Chancellor of Karachi University:

“the police and the intelligence agencies are the hard face of the state, an interaction with them will further consolidate the anxiety and fear in the minds of the students.”

Senator Rabbani stressed that while immediate steps must be taken to address the issue of extremism - proposing a total review of the university curriculum, as well as the implementation of the Senate of Pakistan’s Resolution on restoring student unions - “diverse literary and academic activity” could play in building an effective counter-paradigm. From this it can be inferred that the Senate of Pakistan recognises free speech as a fundamental right that can be a far greater bulwark against terrorism than mass surveillance. This recognition could aid in the development of a major shift in Pakistan’s human rights history.

What is needed is a robust data protection legal regime that prohibits the retention of data by third parties to be later provided to the government. It should explicitly state the exceptions and should specify which information should and should not be disclosed to the government, if the need arises. It should impose a duty on organizations including universities to take specific measures to protect the student’s personal data and penalize them for non-compliance. Further, for less serious cases, there should be a non-mandatory mechanism whereby the university should decide if it would be necessary and proportionate to disclose information to LEAs.

Published by: Digital Rights Foundation in Blog

Comments are closed.