Year in Review: PECA

Today (August 11) marks one year since the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2016 (PECA) was passed by the National Assembly. When the law was passed the government made certain promises and civil society actors expressed fears regarding the potential for clampdown on civil liberties. To mark this occasion, Digital Rights Foundation has created a timeline of events since the Act was passed and a short report on the Act’s progress.

The PECA was a long time coming, several versions of the Bill had been presented to the national assembly and senate. The Bill had four major iterations, an April 2015 version, a September 2015 version, an April 2016 version and the final version passed in August 2016. Much ado was made of the fact that around 50 amendments were incorporated, however these amendments still left some of the major criticisms unaddressed. In fact, several key government officials have complained that the amendments to the Bill have rendered it ineffective. The Minister for Information Technology and Telecommunication (MoITT), Anusha Rehman, has gone on to say that “Cyber Crime Law has been weakened and not remains even 40 percent of the original draft, after some NGOs [who had vested interest] raised the issue while quoting attack on freedom of expression”.

Beyond the rhetoric, a deeper analysis of PECA and its accompanying implementation structures reveals an ineptitude and unwillingness on part of the government to make online spaces safer. In fact, the Act has given ample leeway to the government to silence dissent and threaten opposition parties.

The lack of transparency that marked the deliberation and passage of the Bill has continued into its implementation. The FIA and PTA have not been forthcoming with information about the progress of the Act. In fact, the FIA, the designated investigative agency under section 29 of PECA, has failed to fulfill its responsibilities to report under the Act. Section 53 of PECA requires that the FIA submit half yearly reports to both houses of parliament. Senator Aitzaz Ahsan raised this issue in the Senate on July 19, 2017: “Well over six months have gone by, we are now almost coming to one year. Stricto senso speaking, two reports should have been before Parliament. Not a single report is before Parliament.”

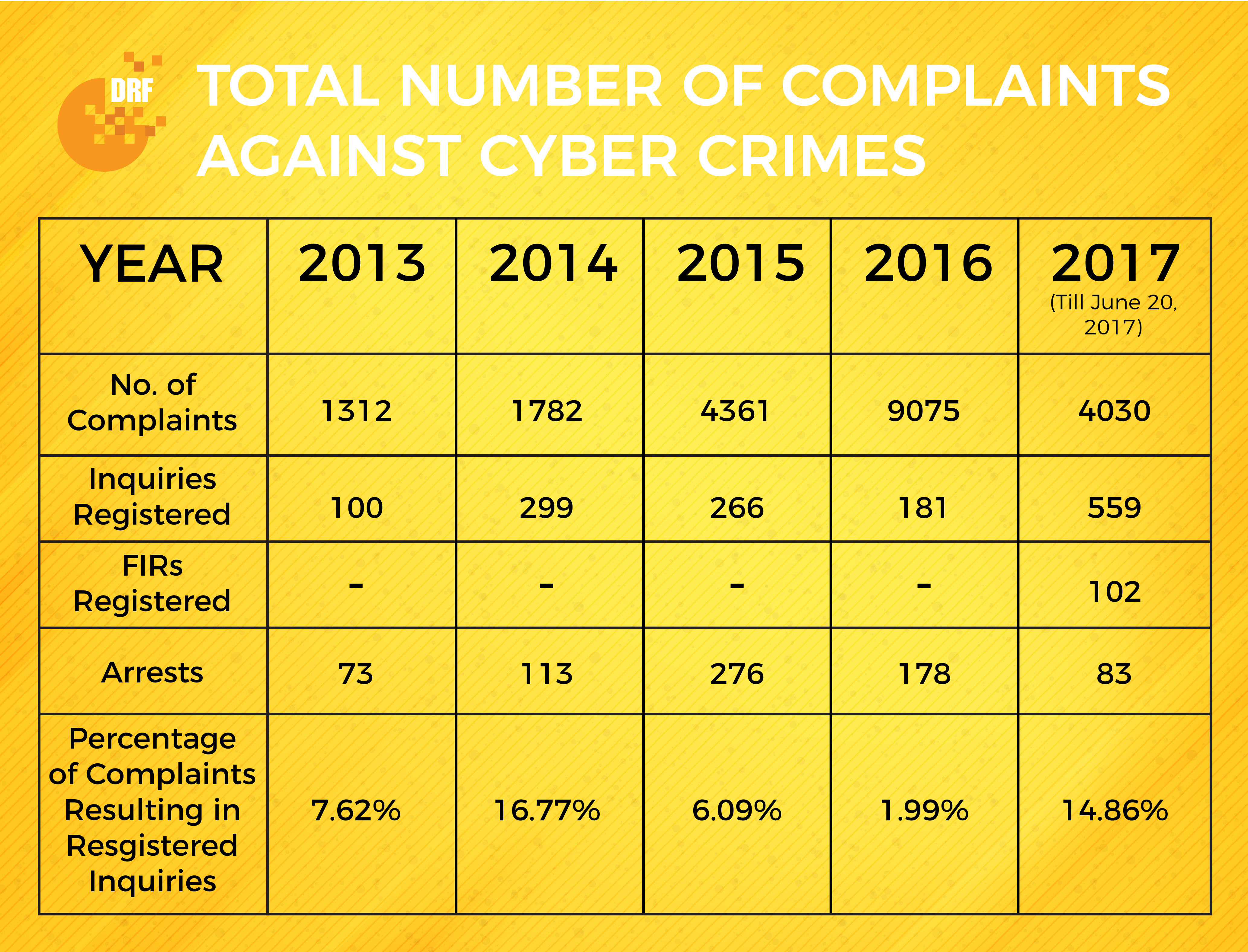

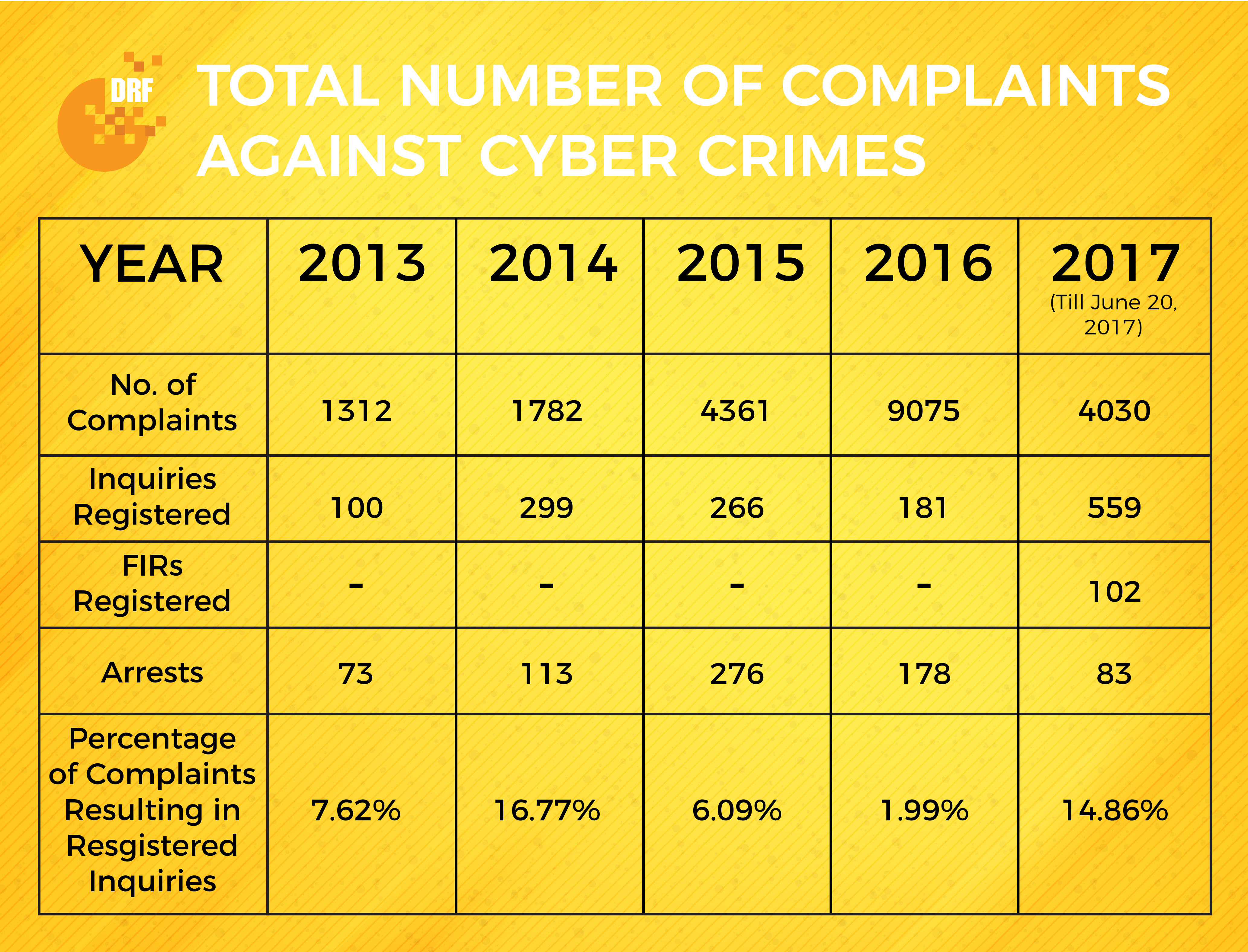

Furthermore, the government’s ability to process cases of cyber crime has in fact worsened since the passage of the Act. There is a discernable problem of capacity at the National Response Centers for Cyber Crime (NR3C) at the FIA as outlined in our Helpline report and articulated by the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) itself. Nothing came of the announcement in October, 2016 that the government was designating Rs. 2 billion for 10 cybercrime police stations and forensic laboratories in the country. Our research on online harassment shows that the promise to “protect” the women of Pakistan from the scourge of online harassment has not been brought to bare as only 15% of those surveyed by us have reported to the FIA or know someone who has. 47% of women feel that reporting to the FIA would be “a waste of time”. The table below echos this lack of trust in the institutions vested with the power to fight cyber crime--overall there is a less than 10% chance that your complaint will lead to a registered inquiry.

Figures for total number of complaints and 2017 have been taken from Senate debates (dated June 19, 2017). The remaining numbers have been provided by reporter Zahid Gishkori.

More long-term data also shows an inability of the FIA to process the huge volume of cases that fall under its jurisdiction. According to official data, 20,180 complaints have been submitted by citizens from 2011 to April 2017. Only 4,501 inquiries were ordered by FIA investigators against over 20,180 complaints. This is a rate of 22.3% overall.

On the other hand, these lack of resources has not discouraged the government from its crackdown on dissent or political opposition. Over the past sixteen months, “some 240 social media activists” faced cases. Furthermore a list of 200 social media activists was forwarded by the Interior Ministry to the NR3C in May, 2017 for “defaming the army”. A majority of the activists who were detained and arrested under this order belonged to opposition parties, further cementing the feeling that this Act is a tool for political victimisation. When it comes to freedom of expression, these sorts of moves by the government are extremely detrimental to free speech as they create a “chilling effect” and result in self-censorship.

Many of the fears put forward by digital rights activists were brought to fruition as there have been several arrests and detentions of political opposition parties and their social media wings. Journalists have been questioned and arrested for allegedly “anti-state” comments online. We are none the wiser when it comes to definitions on what it means to be “anti-state”, “against the ideology of Pakistan” and “anti-army”. These worrying trends were predicted a year ago and it saddens us to report that we, along with other voices within civil society, were right. It was also during the coverage period that Pakistan attained the inglorious distinction of awarding a death sentence for blasphemy on social media.

The government has also revealed its priorities under PECA through its various campaigns. The priority is clearly not to mobilise resources to tackle online harassment, however concerted efforts have been taken to outline the “limits of freedom of expression”. This TV advertisement ran on air during March, 2017:

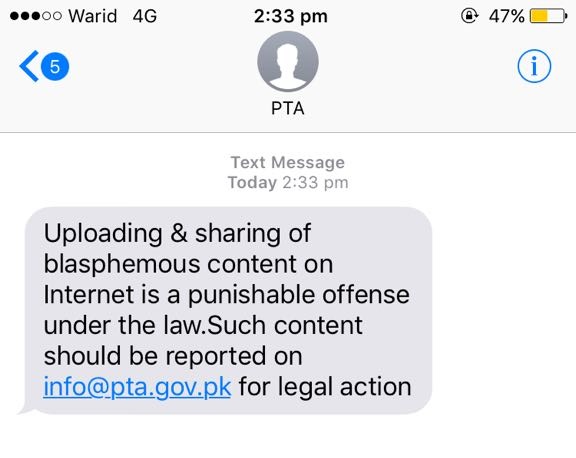

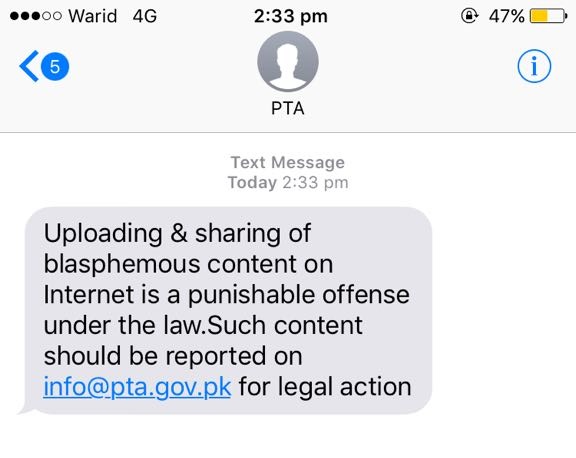

On 9th May, mobiles across Pakistan beeped to receive this message from the PTA:

Mass SMSes were sent to citizens encouraging them to report blasphemous content online to the PTA. On the other hand, the PTA was complaining to the government that it does not have the resources to act on every complaint sent its way. Unfortunately a similar campaign could not be started to discourage online harassment or to report extremist pages on social media websites who continue to operate freely online. It was also in this political climate that the government also dragged its feet at every stage of the implementation process. The Ministry of Law and Justice waited till March 31, 2017 to issue notification on the designated judges to try cyber crime cases. It was only in May that the first conviction under PECA was passed. The MoITT and PTA have, till date, failed to draft any rules for implementing PECA as required under section 51 or to clarify its role in removing “unlawful content” under section 37(2). The FIA has been caught unawares at several times by our Helpline team regarding their own powers and jurisdiction; expressing inability to go into other jurisdictions despite section 1(4) of PECA.

Author: Shmyla Khan